I confess I have made an idol of my mind, but I have found no other.

-Paul Valéry

For every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction.

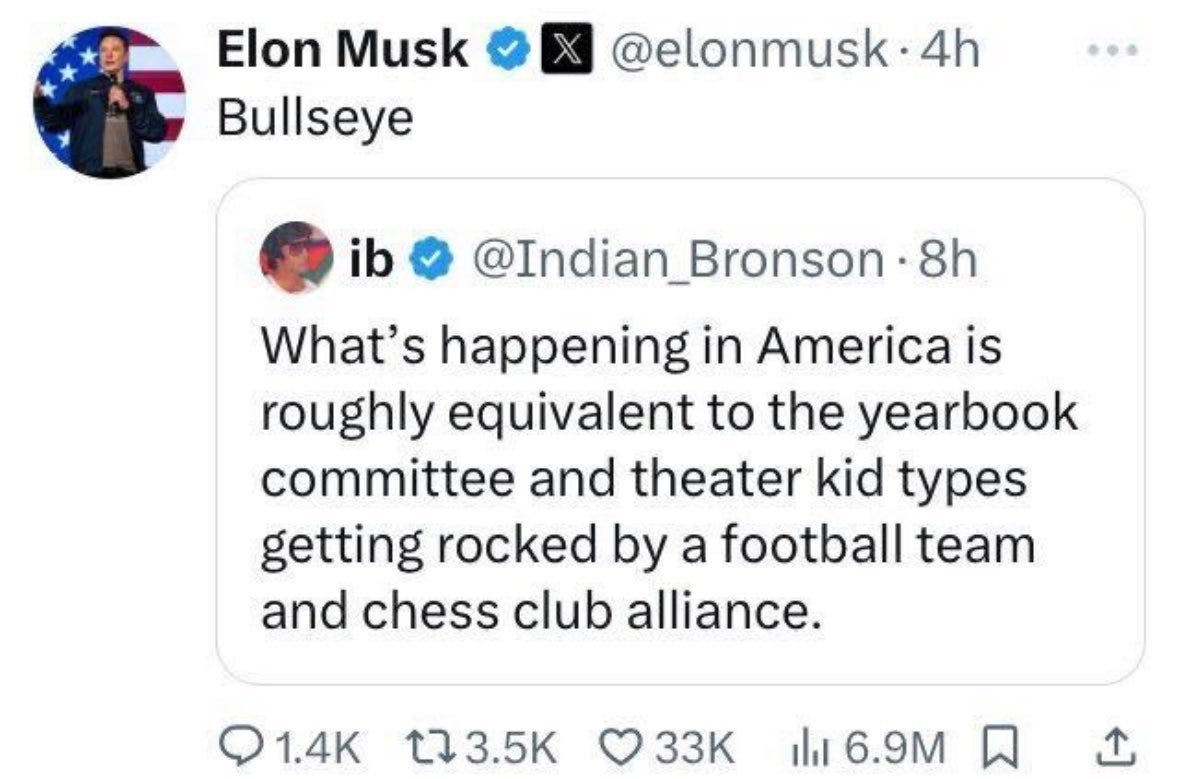

That’s what I thought when Donald Trump was re-elected and the Department of Government Efficiency, led by Elon Musk, started hacking at anything that the new government deemed wasteful whether people, process, or products. Every cut in the name of calculation, every madness in the name of measurement.

In the new government, STEM majors (chess club kids) have teamed up with business majors (football team) to overthrow the reign of English majors (yearbook committee) and sociology majors (theater kids).

What does the football team and the chess club alliance want?

Revenge.

Their view is simple: the government is broken because the math isn’t mathing. The hopeful and humanist model of endless nonprofits has produced waste and corruption without improving long-term outcomes. Harm reduction, laid bare on their spreadsheets, is terminal. STEM majors are aggrieved by this disrespect for numbers. Rather than a violence of empathy (emotional blackmail), we’re now seeing the violence of logic. Elon Musk, general of the STEM rebellion, is the archetype of an aggrieved STEM major. He has decided that his personal beliefs in how numbers need to be treated should be the basis for a new system of STEM-based values to be applied nationally, if not globally. If the benefits of something can’t be measured in this system, the thing needs to be stopped. Gone are the days are soft power. Here to stay is hard data.

On the surface, our new STEM overlords can seem inhuman. But it’s important to understand that whenever a number is named - a statistic, a cost, a program, an output from a group of people - you are hearing a feeling. The aggrieved STEM major hides all emotions inside numbers, which means emotions aren’t valid unless the math is mathing. When the new government lays off tens of thousands of employees, destroys programs that affect millions of people, and rips apart budgets to see what’s inside, the aggrieved STEM majors are in search of nirvana. This nirvana can only be achieved when all the numbers finally add up. The aggrieved STEM major knows emotions are equations and numbers are love. When those numbers don’t add up, the reaction is pain, grief, and anger.

Revenge.

I started thinking about the emotional systems of the aggrieved STEM majors among us when I came across a STEM-minded man from another era who became a poet. His work shows a portrait of someone who believes the rational is beautiful, humans are machines, and the sublime is a system, not a soul. In it, we see a picture of the aggrieved STEM major. And some symptoms of those who might have aggrieved STEM major tendencies.

The Anti-Romantic

What does human ‘fate’ (as you say) interest me? About as much as… the goddess ‘Barbara’ about whom no one has hard and whose name I just invented. It’s the same thing when it comes down to it, can we only work up enthusiasm for the absurd?

- Paul Valéry

French poet Paul Valéry was born in 1871 on the coast of the Mediterranean and grew up in Montpellier. He tried to enlist in the navy, but he wasn’t good enough at math. This is, perhaps, where the aggrieved STEM major mindset began: being told his numbers simply weren’t good enough. Instead of the navy, Valéry went to law school and wrote poetry on the side. By the 1890s, he had served in the ministry of war and became a private secretary for an executive at Agence Havas, the world’s first news agency. Not a bad career track, all in all. But it’s Valéry’s single-minded anti-Romanticism that became his legacy, his equal and opposite reaction that later became a movement. He would be known as the last master of French classical verse. And it all started when he decided to be hater.

To understand Valéry’s anti-Romanticism, it’s important to remember that Romanticism itself was a reaction. In The Cosmic Connection (2024), philosopher Charles Taylor dates the dawn of Romanticism to the 1790s. “Romantics were rebelling against a dead, mechanical view of Nature,” he writes. Romanticism was a reaction to an Enlightenment that seemed to be destroying the magic of the universe with science.

That said, anyone who has read a Percy Shelley poem or followed Wordsworth on one of his walks knows that Romanticism can get a little fluffy. To really feel nature without numbers or science, art got abstract. Mountains had meanings. Trees, flowers, and gardens bloomed with emotion. Wind had an attitude.

Valéry hated it. The Romantics, he wrote, “shunned the chemist for the alchemist. They were happy only with legend or history - that is, with the exact opposite of physics.” As a poet who loved science and math, he described himself as a “grafted being.” His mission was simple: “grafting mathematics onto poetry.” He pursued a new level of clarity with his language, explaining, “I forbade myself from using any word to which I could not attach a definite - conscious - meaning.” In other words, he wanted his poems to be like equations that made sense.

Valéry found a champion to this mission in Edgar Allen Poe. As Nathaniel Rudavasky-Brody puts it in The Idea of Perfection, a 2020 collection of Valéry’s works, Valéry revered “The Philosophy of Composition,” an 1846 essay where Poe tried to define in “rational terms” how he wrote ‘The Raven.’ Valéry also found inspiration from Poe’s 1847 short story “The Domain of Arnheim”:

I believe that the world has never seen - and that, unless through some series of accidents goading the noblest order of mind into distasteful exertion, the world will never see - that full extent of triumphant execution, in the richer domains of art, of which the human nature is absolutely capable.

Aggrieved STEM majors, take note: it is not cryptocurrency or passive income AI apps that you need to feed your soul. It is nothing less than the pursuit of a fully triumphant execution that drives human nature to new heights. Self-fulfillment, as it turns out, may be in form. Not function. Steve Jobs was right all along.

Valéry’s vision for his grand work, his masterpiece, he wrote in 1933, “is for me the knowledge of the work itself - of the transmutation - and individual work are its local applications, particular problems.” That’s right. He thought of his masterpiece in modular terms. Every poem was a program to the greater system. Every artistic achievement an API connecting to some pure source.

Valéry’s quest for the perfect clarity, as any aggrieved STEM major may recognize, is a quest for a system that runs in a perfect eternal flawless loop that would go on without him, explore and expand upon itself like an algorithm. In 1921’s The Angel, Valéry puts this machine of the sublime like this:

And he examined himself in the universe of the marvelously pure substance of his mind, where ideas all lived at equal distance from each other and from himself, and in such perfect harmony and so quick in their correspondences that were he to disappear, it seemed that the system, sparkling like a crown, of their simultaneous necessity, might continue to exist alone in its sublime fullness.

Valéry took two important steps to pursue this perfection of form:

1. Listened to Richard Wagner.

In 1891, a friend introduced Valéry to German composer Richard Wagner. This led him to learn about probability theory and logic. He read Electricity and Magnetism from James Clerk, Constitution of Matter from Lord Kelvin, as well as Bertrand Russell and Nikolai Lobachevsky on geometry. There is no mention of Nikola Tesla in the biographies I’ve read, but it is undeniable that this bizarre catalog makes Valéry a certified steampunk poet.

2. Had a mental breakdown.

In the proud tradition of other French intellectuals (Blaise Pascal comes to mind), it was a mental breakdown that changed Valéry’s life. The year was 1892. A lightning storm raged outside his bedroom at night. Writing to a friend about the fateful night thirty years later, Valéry recalls:

Nothing but high frequency - in my head as well as in the sky. I was endeavoring to break down all my first ideas, or Idols; and to break with a self that was incapable of achieving what it wanted, and did not want what it was capable of.

Valéry basically saw lightning, thought about the limitless potential of human nature, and became charged forever after with a belief that we are nothing but moody, magical electrons. Again, this is some steampunk stuff. As he wrote in 1898’s Monsieur Teste:

I imagine there is in each of us one atom more important than others, made up of two particles of energy which would very much like to break away from each other…nature joins them together forever, though they are furious enemies.

Valéry’s poetry tried to follow the “psychological sensation of consciousness” in search of what he called “a continuous music.” Rudavsky-Brody cites Valéry to explain that his poems were not about the piece but “that prolonged hesitation between sound and meaning.” It was all about precision, patience, literature as a calculation and an exercise. About art as programming for the soul. After all, he explained, art is “a machine intended to excite and combine individual formations [in a] category of minds.”

This, then, is how he could “break with a self that was incapable of achieving what it wanted, and did not want what it was capable of.”

Stems of Truth

There are only 2 things that really matter, that ring true - one that I call Analysis and which has ‘purity’ as its object; the other that I call Music and which composes that ‘purity.’

-Paul Valéry

Just as Romanticism was an equal and opposite reaction to the Enlightenment, the turn of the twentieth century saw a return to reality that would eventually emerge in the broken-nose prose of Hemingway and Yates. Writing for The New Yorker, Benjamin Kunkel explains that Valéry’s poetry serves as a “crucial link between nineteenth-century symbolism and the movement that followed.” Kunkel’s essay was enough for me to buy a collection of novel-like fragments, Monsieur Teste (1896) freshly interpreted by author Ryan Ruby and translator Charlotte Mandel. In Monsieur Teste, the eponymous protagonist is a man without emotion, a man who thinks like a machine. And, from what I can tell, an alter ego for Valéry himself. Half of the chapters read as if lifted wholesale from journal entries. It is a fascinating and occasionally listless look at what it feels like to be an aggrieved STEM major struggling to put all the world, all the heavens, into a system that makes sense.

In Monsieur Teste, I recognized the most common symptoms of an aggrieved STEM major that I’ve seen in friends, family, and myself. So, if you’re curious, come back on Monday to learn Litverse’s seven signs that you or a loved one may be an aggrieved STEM major.

In “7 Symptoms of the Aggrieved STEM Major,” come back to learn in a fun and exciting way that there is no real relief from grief in a less-than-ideal system. As Valéry proves, there is no cure to this. Only poetry.

Impatient for pieces on other French literary legends? Enlighten your day with Litverse classics such as:

Clever piece. Deep insights here if one doesn't jump to any one given conclusion.

I dunno, maybe I missed the plot, but ol' Pablo doesn't sound much like a man motivated by grievance. The aggrieved obsess over the minute and the parochial at the expense of the bigger, more fully comprehensible picture - and it seems like that's the exact mentality that Paul's dismissive of, where the Romantics are concerned.

But maybe he's somewhat hypocritical on the subject, and is in fact as much of a petty score-settler as those he purports to critique. He'd be far from the first 😄