I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

-Robert Frost, The Road Not Taken

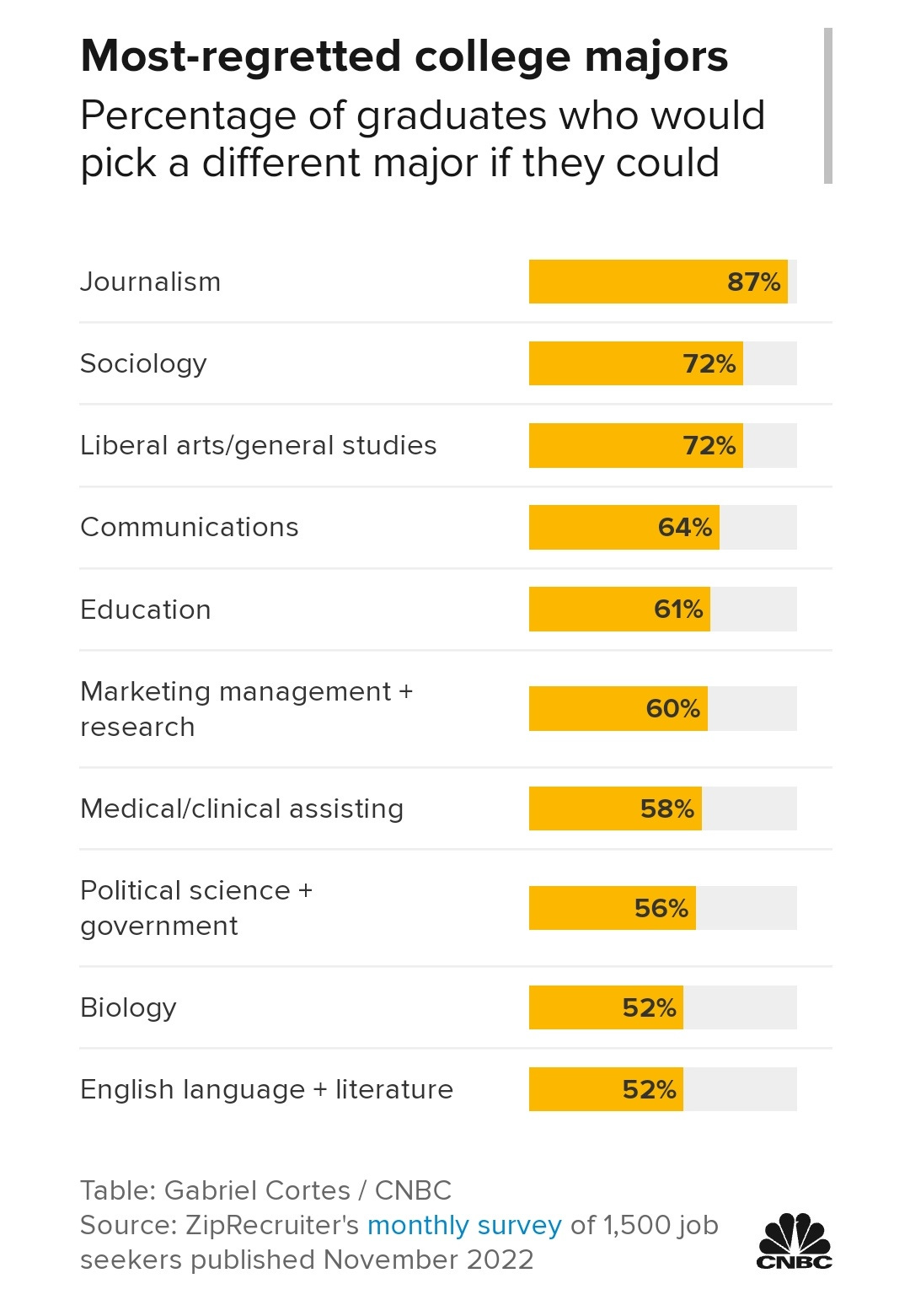

A survey this month found that 87% of journalism majors regret their choice of major. Sociology and liberal arts majors are next - three-quarters of them wish they could take it all back.

We’ve all experienced regrets. But to look back down a road you took, wishing you had taken a different direction four years ago, must be painful. Are you erasing all four years of college? Is the regret isolated simply to the major and every other event in your college life is the same? It is impossible: lives are grown in gardens, not made-to-order in factories. We can’t rip out a root and expect the rest of the plant to thrive, or even survive.

But without regret, we turn into creatures that treat every instinct like destiny. We become animals without shame and without empathy. In The Great Gatsby (1925), Fitzgerald captures that mechanical mercilessness when narrator Nick Carraway reflects on the tragic events of the book:

They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.

Regret is humanity’s anchor in that vast carelessness.

Nostalgia on Demand

If regret represents the bad memories we want to forget, nostalgia represents good memories we want to hold and repeat. There’s nothing new about painting our pasts gold and showing them off. The most powerful industries, always, have been the ones that guarantee nostalgia. Yet even nostalgia can cause pain.

As Don Draper puts it in “Mad Men:”

In Greek, ‘nostalgia’ literally means ‘the pain from an old wound. It’s a twinge in your heart, far more powerful than memory alone. This device isn’t a spaceship, it’s a time machine. It goes backwards and forwards, it takes us to a place where we ache to go again.

The sales pitch is about a new projector. Don shows off the pictures of his happiest moments with his family and sees paradise in the painted tapestries of his life. The projector stops spinning and he’s back in the dark. Unable to overcome the regret of nostalgia with anything other than oblivion, he goes back to living the only life he knows. He makes the sale.

Mad Men explores Draper’s regrets for season after season. We see Draper experience every peak and valley but never quite “get over it.” Draper knows that regret is inevitable, because loss is inevitable. But he is doomed by his animal instinct to try and forget regret by always running from it, not looking down the road behind him. If only he had read some Proust. Then he would know that regret teaches us that even memory is pain, but pain is discovery.

In The Shadows of the Self

In Within a Budding Grove, the second volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1909-1922), Proust’s narrator learns the value of regret with a famed Impressionist painter by the name of Elstir, who is already famous for his tips about finding focus. Turns out, Elstir has tips about regret, too.

The conversation begins when the narrator of Within a Budding Grove points out a painting that makes Elstir shy, maybe even ashamed. It’s a painting of a woman our narrator recognizes as Odette de Crecy, who married into nobility with a manipulative charisma that leaps off the page of the first volume in the series, Swann’s Way. Her life before marriage, however, was that of a mirage of mistresses, all of them with different faces but many of them being paid for the pleasure of their company.

To make matters worse, it’s a scandalous painting. Odette is so young she’s barely recognizable. Our narrator even suspects that Elstir may have, long ago, done something dishonorable with her. It’s hard not to avoid, in knowing that Elstir is partly inspired by London-born James Abbot McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Gilded Age painter better known as Whistler, looking at, stylistically, what Proust may have had in mind.

The narrator makes a realization: during the salons where Odette had met her husband-to-be, there had been stories of a painter who had been a disreputable man. A creep. A pervert. An industry giant who abused his power. He suspects Elstir.

Could it possibly be that this man of genius… this recluse, this philosopher with his marvellous flow of conversation, who towered over everyone and everything, was the ridiculous, perverted painter?

He decides to ask. Elstir admits it without hesitation. This is when Elstir dwells on the nature of regret and the power of pain:

There is no man, however wise, who has not at some period of his youth said things, or lived a life, the memory of which is so unpleasant to him that he would gladly expunge it. And yet he ought not entirely to regret it, because he cannot be certain that he has indeed become a wise man - so far as it is possible for any of us to be wise - unless he has passed through all the fatuous or unwholesome incarnations by which that ultimate stage must be preceded.

In comparing the ghost of himself in an old reality, Elstir draws strength. Shame and regret and mistakes, he tells our narrator, are the tools of self-creation:

I know that there are young people, the sons and grandsons of distinguished men, whose masters have instilled into them nobility of mind and moral refinement from their schooldays. They may perhaps have nothing to retract from their past lives; they could publish a signed account of everything they have ever said or done; but they are poor creatures, feeble descendants of doctrinaires, and their wisdom is negative and sterile.

As Elstir says:

We do not receive wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can make for us, which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world. The lives that you admire, the attitudes that seem noble to you, have not been shaped by a paterfamilias or a schoolmaster, they have sprung from very different beginnings, having been influenced by everything evil or commonplace that prevailed round about them. They represent a struggle and a victory. I can see that the picture of what we were at an earlier stage may not be recognisable and cannot, certainly, be pleasing to contemplate in later life.

This suggests something beyond absolution: achieving purity from the rot of regret in the totalitarian triumph of surviving ourselves. Coming to peace with the past isn’t possible, but it is possible to transcend it by expressing it:

For it is a proof that we have really lived, that is in accordance with the laws of life and of the mind that we have, from the most common elements of life, of the life of studios, of artistic groups - assuming one is a painter - extracted something that transcends them.

Elstir made many choices that he regrets, but he believes that this was the only road he could follow to achieve growth. He never gets over it, he puts it into the work that is his life. Because, deep down, he believes that getting over regret, never feeling it, is to lose your definition for inspiration. Because what if regret is an old friend we hold close out of habit and to forgive ourselves would be like poking our eyes out, blinded by the indulgence of our mercy?

Elstir isn’t claiming that transcendence is redemption. There is no way to achieve a blank state, but by understanding our flaws and listening to those lost causes calling from the void, we find truth in the contours of the emptiness, not just phantoms of what could have been, but never was.

In the sublime scale of a life lived, regret is as precious as nostalgia. The weight is the same. Forgiveness is an act of self-sacrifice that cleanses the soul and helps you get over regret. Protecting your mind from anything that may cause you regret is another. But they are both part of the same road. The other road, the one not taken as often, is a life spent wrestling with past sins in perpetuity to eternally find different answers within the black ocean of the self, waiting with each new act of self-creation to see what bright shells, painted with the colors of older tomorrows, wash ashore in the dawn.

There's something deeply resonant here. I've wrestled with the question of what to do with regret for what feels like my whole life so far. Missed opportunities, stupid choices, wasted time... The wrong way is to fantasize about what life would be like if I'd just [insert alternate history here].

But then, the sum of who I am today must be at least in part a product of this wrestling. Do I seek absolution? I don't know. Transcendence? Again, I'm not sure what that means. What I want is to be fully who I am, growing deeper and taller with each passing year. Attainment of greater virtue for the sake of attaining greater virtue.

To contextualize the deepset thorn of regret as a useful tool in that aspiration is an angle I hadn't quite comprehended before.

Always nice to see you wrestling with questions of identity and self, and channeling your ear for figurative language in the process. Like J.E., I always find new angles on perceiving life through your work: thanks as always for the thought provocation 🤝