I am wagering on man, not on God.

- Jean-Paul Sartre

In February 1973, at age 68, French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre had a stroke. It is very likely no one was surprised. As a co-parent of existentialism, Sartre had decided a long, long time ago that his health was to be used in the service of writing. He worked in thirty-hour shifts fueled by meth pills and cigarettes. As The New Criterion explains, he saw literary work as “an absolute end.” Anything that helped was worth the cost. According to biographer Annie Cohen-Solal, Sartre passed each day with:

two packs of cigarettes, several tobacco pipes, over a quart of alcohol (wine, beer, vodka, whisky etc.), two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, a boat load of barbiturates, some coffee, tea, and a few “heavy” meals (whatever those might have been).

In an interview with Michael Cenat in 1975, Sartre at Seventy, Sartre recalls the routine of his fifties when he wrote The Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960):

I worked on it ten hours a day, taking corydrane - in the end I was taking twenty pills a day… the amphetamines increased the speed of my thinking and writing so that it was at least three times my normal rhythm, and I wanted to go fast.

What’s cooler than that? Isn’t that what existence is all about?

Fault V. Fate

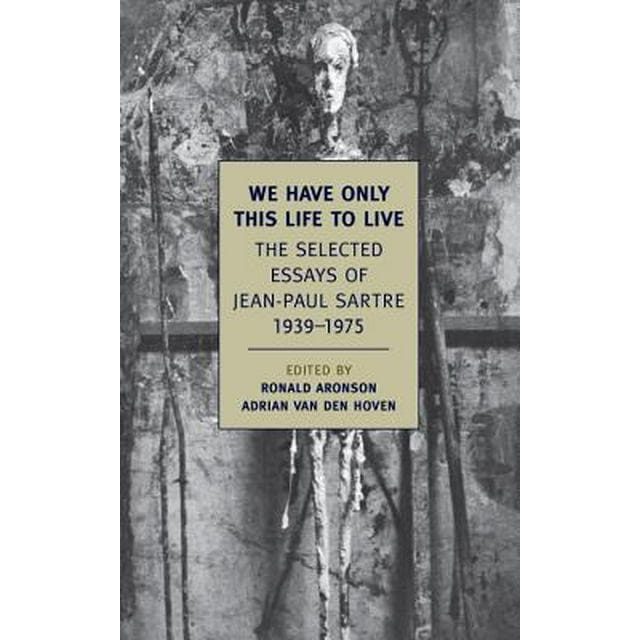

If you don’t have religion, you might as well have a philosophy. I picked up We Have Only This Life to Live, a 2013 collection of Sartre essays, with this idea in mind. Sartre’s existentialism justifies excess as a way to reach your truth. In other words, it’s a philosophy any addict can get behind. Radical, sloppy optimism. That’s what I expected.

It’s not what I got. After reading Sartre’s interview with Cenat, I had to face the facts: there’s something immature about existentialism because there’s something emo about existentialism.

After all, most of us probably know it from “existential dread,” the go-to phrase for hopelessness and emptiness when you’re feeling spicy or multisyllabic. According to an AI from a search engine:

Existential dread is a profound, deep-seated psychic or spiritual condition of insecurity and despair in relation to the human condition and the meaning of life...

This existential angst arises from the awareness of mortality and the absence of inherent meaning in existence

If you’re an existentialist, the so-called “absence of inherent meaning in existence” is the appeal. Without meaning, you can’t blame yourself for anything. You are free from fault, because from emptiness comes the fate of the void. Existential fate is freedom: if there is no actual meaning to anything, life is a blank slate. You get to make your own meaning. Sartre’s meaning was writing. His destructive habits helped him write. This was the existence he lived and so therefore it was his meaning. He wrote, therefore he existed.

As Sartre explains:

In a certain sense, all our lives are predestined from the moment we are born. We are destined for a certain type of action form the beginning by the situation of the family and the society at any given moment… I do not mean to say that this sort of predestination precludes all choice, but one knows that in choosing, one will not attain what one has chosen. It is what I call the necessity of freedom.

Unmarried and childless and friendless at seventy, Sartre explains in Cenat’s interview:

I have written, I have lived, I have nothing to regret.

The necessity of freedom, in Sartre’s view, is the absence of regret and when you have no regret, you can not judge yourself or others:

I have not been disappointed by anything. I have known people, good and bad - moreover, the bad are never bad except in relation to certain goals.

This line of thinking ends at a natural apathy. At seventy, Sartre has no advice for rebels who want to overthrow the system. When Cenat explores the topic of revolution, the idealistic communist Sartre responds:

Who, or what, should I be rebelling against?

- It’s just that things are the way they are and there’s nothing I can do about it,

Are you unhappy? Guilty? Sad? Addicted to alcohol and/or/also drugs? In Sartre’s senior citizen existentialism, freedom starts by accepting fate instead of fault. An apologist for Mao’s communism and Stalin’s socialism, Sartre believed that to be free, we have to free ourselves from alienation. But in embracing predestination to accept our excess and the excess of others is to walk a lonely road. The freedom of our addictions in the place of structure is what make us lonely in the first place.