Last month, a survey found that nearly half of AI researchers believe there’s more than a 10% chance of human extinction because of the work they’re doing. Despite the risks, these researchers continue carrying out their possibly apocalyptic work.

How, some people wondered, do these researchers justify their efforts?

Maybe it’s simple: the human attitude toward technology is ambivalent, but our fascination is genuine.

Legendary science fiction author Kurt Vonnegut, whose career spanned 50+ years, would likely agree. He shared the sentiment in a 1973 interview when discussing the inspiration for his debut novel about automation, Player Piano (1952):

I was working for General Electric at the time, right after World War II, and I saw a milling machine for cutting the rotors on jet engines, gas turbines. This was a very expensive thing for a machinist to do… So they had a computer-operated milling machine built to cut the blades, and I was fascinated by that. This was in 1949 and the guys who were working on it were foreseeing all sorts of machines being run by little boxes and punched cards. Player Piano was my response to the implications of having everything run by little boxes. The idea of doing that, you know, made sense, perfect sense. To have a little clicking box make all the decisions wasn't a vicious thing to do. But it was too bad for the human beings who got their dignity from their jobs.

Vonnegut, too, was both fascinated by the process in which companies replaced people with a “little clicking box” in such an unintentionally hostile way.

Let’s just hope that our AI researchers of today don’t become as defeated as Vonnegut in their golden years, an attitude made clear in one of his last public appearances when Vonnegut, eighty-two, appeared on The Daily Show in 2005 with Jon Stewart.

He opens by telling Stewart that he wants to sue cigarette companies, because the packages promised that cigarettes would kill him and they didn’t. He then offers his recommended fate for humanity:

Yes, well, I think we are terrible animals. And I think our planet’s immune system is trying to get rid of us and should.

It’s not the truth that hurts. It’s the “should.”

As one of the country’s premiere sci-fi satirists for more than fifty years, Vonnegut laughed at the absurdity of it all until the end of it all. But his final remedy for his own terminal alienation seemed to be the resting state of resignation. He was, as his last work tells us, a Man Without a Country (2005).

This makes me wonder if we misinterpret Vonnegut as a satirist. The label “black humor” is used to describe something both horribly tragic and horribly funny. That’s probably more accurate. Sometimes, even the funny parts of his books are too biting and too real. There’s a glimmering love of laughter, but there is never a sense of triumph. Sometimes, in the case of Cat’s Cradle (1963), all of humanity is actually murdered by their own stupidity instead.

Even Vonnegut’s death reflected the black and white duality of his dark humor: Kurt Vonnegut died trying to walk his dog.

As described in a paper from The Vonnegut Library:

Taking his little dog out for their usual walk, Vonnegut apparently got tangled up in his pet's leash and fell face forward onto the sidewalk. The resulting blow to his head sent him into a coma from which he was unable to recover. He died on April 11. He was 84.

Disappearing into the predestination of his own nihilism, Vonnegut left us with a lingering question: is technology a force for good or for evil?

His work explored the same question in a different way: When, exactly, is our point of no return as a species?

Of Trauma and Technology

When we think of “Big Tech” in 2022, General Electric never comes up. Instead, we define Big Tech by the companies that control and manage and optimize the virtual channels in which we live today.

For example: Apple, Google, and the artist formerly known as Facebook (Meta).

Americans can’t agree on much, but there’s one thing we all have in common: we don’t trust these companies. More than 86% of people say they don’t trust Big Tech. These are Big Words coming from a country where most consumers spend five to six hours a day on our phones.

Technology, in this sense, is only as evil as our use of it. And we love to use it.

In the era before the Internet, the threat of Big Tech wasn’t about software. It was about hardware: advanced hardware that murdered millions of people with fire and shrapnel. Or, in the era of World War 1, hardware that caused the chemical asphyxiation of 100,000 people.

Slaughterhouse-Five, published in 1969 (the same year as Woodstock), was Vonnegut’s sixth and most famous novel. It’s a story centered on his own experience inside an apocalypse and details the firebombing of Dresden in 1945, when Allied planes dropped bombs that burned hundreds of thousands of German citizens alive.

Vonnegut, 23, hid in a freezer. When he walked outside, he saw a melted hell caused by the impersonal horror so carelessly generated by technology. It took him more than twenty years to process the experience into prose. The result, Slaughterhouse-Five, is a funny, visceral, irreverent, tragic account of a massacre caused by hardware. Yet we consider Slaughterhouse-Five an antiwar novel, not an anti-technology novel.

Vonnegut’s debut, Player Piano (1952), is what captures the more insidious nature of technology as it evolves from tool to threat simply by humanity’s application of it. The novel tells the story of an automated society in which all trade and craft industries have been taken over by machines and those who manage them.

As Wikipedia puts it:

The widespread mechanization creates conflict between the wealthy upper class, the engineers and managers, who keep society running, and the lower class, whose skills and purpose in society have been replaced by machines.

This summary, written about a novel from the fifties, can easily flavor the scorn heaped on Big Tech in this millennium. The only difference, perhaps, is that tech workers, obsessed with virtualizing every process, are certainly not the ones that “keep society running.” At least not in the fundamental sense of something like plumbing. Or better yet, barbering.

It’s the barbers in Player Piano I remember the most. As Vonnegut’s star barber Homer Bigley explains, cutting hair was at first too hard for machines to master. Even after doctors and dentists had been replaced, barbers were still human.

Machines, as Bigley explains, separated the men from the boys. But then a barber surrenders the secret of separating hair from scalp and it all comes crashing down:

Anyway, I hope they keep those barber machines out of Miami Beach for another two years, and then I'll be ready to retire and the hell with them. They had the man who invented the damn things on television the other night, and turns out he's a barber hisself. Said he kept worrying and worrying about somebody was going to invent a haircutting machine that'd put him out of business. And he'd have nightmares about it, and when he'd wake up from them, he'd tell hisself all the reasons why they couldn't ever make a machine that'd do the job - you know, all the complicated motions a barber goes through. And then, in his next nightmare, he'd dream of a machine that did one of the jobs, like combing, and he'd see how it worked clear as a bell. And it was just a vicious circle. He'd dream. Then he'd tell hisself something the machine couldn't do. Then he'd dream of a machine, and he'd see just how a machine could do what he'd said it couldn't do. And on and on, until he'd dreamed up a whole machine that cut hair like nobody's business. And he sold his plans for a hundred thousand bucks and royalties, and I don't guess he has to worry about anything any more.

The service economy is decimated. What’s left to do for a workforce with skills forced into obsolescence but to rebel? At the end of the book, the masses rise against the machines. They call themselves “Luddites.”

A half-century later, in Man Without a Country, Vonnegut, a man who only wrote on a typewriter, identifies himself as a Luddite:

I have been called a Luddite. I welcome it. Do you know what a Luddite is? A person who hates newfangled contraptions.

Did Vonnegut hate technology?

Yes.

His engineer’s fascination with how things work persisted through his life, but Vonnegut’s ludditism guided the hopeless humor in his novels for decades. Technology is only as much a threat as the creators and managers behind it. These fallible humans, as Vonnegut says in his interview with Jon Stewart, are the world’s “terrible animals.”

To fight the technology we find most threatening is to fight ourselves.

As one paper puts it:

In Player Piano, the EPICAC is not necessarily the enemy of people, but once it is used as a means of pigeon-holing people and defining their worth, it does become dangerous. In Cat’s Cradle, ice-nine is not itself dangerous, it is just a substance that raises the freezing temperature of water. It is only when people get involved, that its deadly uses are uncovered.

I didn’t know what “luddites” were before reading Player Piano. After reading through the novel, I realized that ludditism is a perfect attitude for any era adjusting to radical changes that seem, almost, like they could bring about the apocalypse. It’s an anti-technology ideology that offers many arguments and zero victories.

Legend of the Luddite

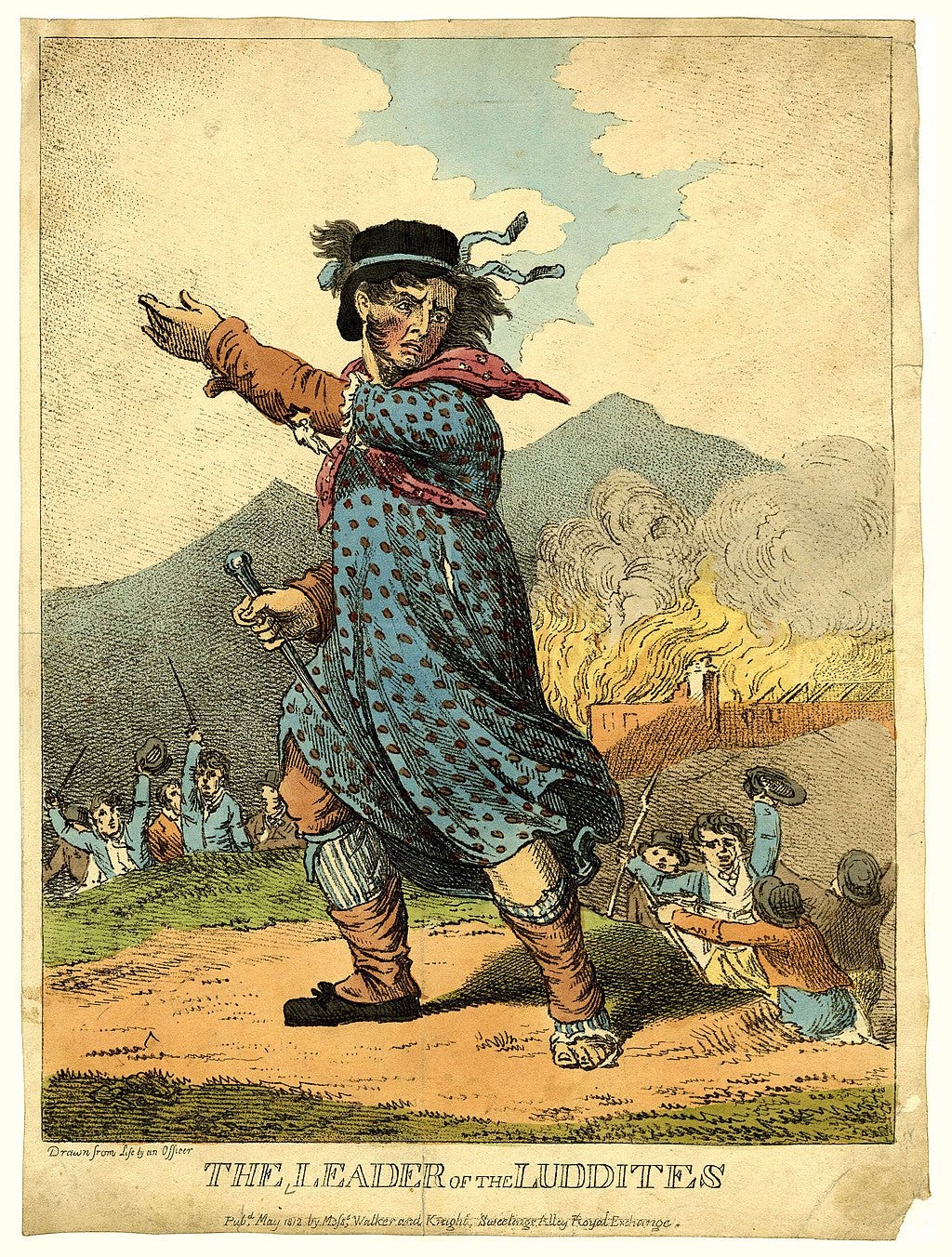

The term “Luddite” originated from an Englishman named Ned Ludd, pictured above as a demigod patterned by polka dots. Ludd supposedly lived in the late 1700s and made his living as a weaver until he was whipped for idleness and rebelled against his conditions.

There is no proof of his existence, but the tales of Ned Ludd inspired British weavers and textile workers of the 1800s to destroy the textile machines that empowered unskilled machine workers to reproduce the very goods they crafted with love and care and livable wages. We could possibly view this as the final death knell of artisan guilds, which in time would be replaced by unions or, if fabrics and sculpting and art was involved, Etsy.

Myth or man, Ned Ludd granted the Luddites of the 1800s - and Vonnegut’s rebels - a namesake for that itchy hostility that so many people feel toward new technology: luddites.

Luddites criticize technology as science sacrificing people for progress, but it’s taken for granted that this is a primitive and regressive attitude. There’s even a catchy phrase that economists deploy against these anti-technology types when they question whether new systems may threaten legacy systems: “the luddite fallacy.”

Few other beliefs are so thoroughly dismantled by the word “fallacy.” One has a hard time believing “communism fallacy” or “capitalism fallacy” or “Christianity fallacy” would so hobble an ideology.

But no one wants to be a luddite, because no one wants to be irrelevant because to be irrelevant is to be useless and to be useless is to be stupid.

Calling anything “a luddite fallacy” is a handy stiletto of an argument. It’s an easy way to sound confident in the future and parry any charges of the negative impacts of technological progress with it. Netscape founder Marc Andreessen used it in 2015 when he said that machines wouldn’t take people’s jobs.

Admitting to Ludditism is admitting to pessimism and even confessing there may be consequences to our righteous march for progress. It’s an understandably sensitive topic in societies built on preaching that progress is gospel. Vonnegut always knew that.

He laughed at the arcane architecture of progress.

He feared our addiction to it.

But what he never truly explained is why he dreaded it all so much until a letter to a high school class right before his death.

Optimization Addiction

There’s a simple test to explain the impact of technology:

Think about something.

Turn on your phone.

What are you thinking about now?

Our connectedness streamlines our thoughtfulness. Our thoughtfulness creates our beliefs, our ideas, our feelings, and our reactions and actions.

Or, as Homer Bigley the barber would say:

Everything's promotion. Ever stop to think about that? Everything you think you think because somebody promoted the ideas. Education - nothing but promotion.

Our dependence on technology is unavoidably true.

But how often do we forget that our control over it is our own?

Where is your phone now?

How many tabs do you have open on your browser?

Humanity’s discipline dissipates when we become disciples of our devices.

Vonnegut’s ludditism wasn’t founded in the belief that technology would destroy the world. It was founded on his belief that humanity would fail to recognize the way it transformed us, all, to little “clicking boxes” that no longer recognized our role in that world.

In searching for the meaning behind Vonnegut’s beliefs, I came across a letter he wrote to a high school class in 2006, a year after his appearance on The Daily Show.

The project had been simple: a high school class wrote letters to their favorite authors. Kurt Vonnegut wrote back, on his typewriter, with what we could call a clarion call for Being:

Here’s an assignment for tonight… write a six line poem about anything, but rhymed. No fair tennis without a net. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it or recite it to anybody… tear it up into teeny-weeny pieces, and discard them into widely separated trash receptacles. You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem…

You have experienced becoming.

Did Kurt Vonnegut hate technology?

Not if he believed that everything, in essence, was part of our Being. He just hated how eagerly, how easily, we can allow that Being to merge with the systems we create, creating a life where the consumption of progress consumes our imagination.

In Player Piano, we find that the meaning of humanity is destroyed by the machines that take jobs but what automation really does is remove humanity’s manifestations so clinically that it makes it seem that our sense of purpose was never necessary in the first place. Today, we find it in the mathematics that calculate what metaphysical vision we may want to see next, based on what simulated the feelings we liked best in the past. It’s a safe life to find purpose on the factory floor of that machinery, where we only see the facility of our interiority, not the holiness of it.

What Vonnegut wanted to tell the world, always, is that the act of creation is the cultivation of our own miracles in the never-ending blooming of Becoming. It is wonder and dreams made real, through the simple act of imagining other worlds that are all our own.

Did Vonnegut really hate technology? Did he really hold no hope for the world?

All we can see for sure is that he believed that it was still, despite every apocalypse behind us and in front us, a miracle.

The AI researchers who think there’s a risk of their field bringing upon another apocalypse are building a different world, one way or the other. Our fear of it could, like we may say about all Luddities, be a fear born of a limited imagination, an imagination playing in the current paradigm as professionally pointless as a player piano, producing a prodigious tune of predictable purpose.

No matter what we may wonder, Vonnegut left us to wonder and wander.

When asked about how his perspective in Slaughterhouse-Five could serve as guidance to readers, he responded:

You understand, of course, that everything I say is horseshit.

And yet, he’s also the author of a being addressing new beings as they are born, imparting lessons on how to live:

There's only one rule that I know of, babies—God damn it, you've got to be kind.

Could a machine ever feel like that?

Dhoreena's illustration is 🔥🔥🔥 too! We the people want more Lucey-Lucey collabs 🙏

Vonnegut is an endlessly fascinating figure. I think surviving the Dresden fire-bomb apocalypse with his body, soul, and mind intact gave him an absurdist God's-eye view of our species; he seems constantly caught between the impulse to make us love each other, and the knowledge that the whole project's futile. And the man was prescient as all hell. What is modern life but addiction to tech conveniences, coupled with revulsion at their downstream effects?

"Welcome to the Monkey House" has some classic short stories along with good Vonnegut esoterica if you're interested - I'm planning on using it and a Bradbury collection I got from Carla's dad extensively when we study sci-fi and speculative fiction in Creative Writing this year.

Great prose plaudits are in order for "handy stiletto of an argument" 👏👏👏