Ernest Hemingway: Macho Cat Dad

When insecurities are our passions

When I first started reading Ernest Hemingway, I was in Florida’s Downtown Disney for college break. During the day, I read manly adventures. At night, I drank vodka from a Gatorade bottle and beat the high score on the unparalleled ostrich-knight flying simulator that is 1982’s arcade sensation, “Joust.”

I was eighteen going on nineteen: the same age as Hemingway when he served in Italy during World War I as an ambulance driver. He arrived in 1918. A month into his tour, a trench mortar exploded in front of him. With over two hundred shrapnel wounds in his legs, Hemingway carried an injured comrade to safety through a maelstrom of machine gun fire.

It’s these kinds of experiences that grant him the authority to proclaim philosophies as if they were unassailable truths, as we see in this passage from Farewell to Arms (1929):

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

Hemingway became an author of his own destiny for the rest of his life.

Much of the time, Hemingway could seem like he placed the utmost importance on masculine pastimes and adrenaline-fueled adventures not for the satisfaction of the lifestyle, but the spectacle of it. Manliness in the thirties and forties also helped sell books.

Hemingway’s legacy tangles interminably with the merciless, muscular, and misunderstood prose he produced. Forever after, it’s unclear whether Hemingway, in real life, was separate from his narrators or his characters. This is what gives us the macho portrait so perfectly captured in 2011’s Midnight in Paris.

In college, I considered myself a romantic. Hemingway’s work, so seemingly obsessed with action, made me think of him as less of a writer than his frenemy, F. Scott Fitzgerald. How could a writer like Hemingway truly savor and express the complexity of life with prose so pared, sentences so succinct, and a life lived so savagely unsentimental?

Modern readers receive Hemingway’s testosterone-fueled candor with inspirationally high levels of outrage. In a review of 2021’s documentary, Hemingway, The Daily Beast concludes him to be a “bullying, alcoholic racist.”

Ken Burns and Lynn Novick portray an insecure, vain, depressed, unfaithful, visionary modernist in PBS’s “Hemingway”, and reframe his complicated place in the literary canon.

In this piece, we’re informed that a man who was gunned down in Italy and whose father died by suicide had a “privileged upbringing.” With an estimated nine concussions throughout his life and a swagger that became pathetic with age, the persona of Ernest Hemingway so worshiped for his heroic wartime exploits can seem an anachronism. “Problematic,” as we’re told several times in The Daily Beast article.

I believed all of this unequivocally.

Until I found a book that changed everything: Hemingway’s Cats.

Now, I know I’ve been reading him all wrong.

Life in the Purr Factory

It was in an open-air bazaar of trinkets and oddities in the Florida Keys that I found Hemingway’s Cats. As a cat owner, it was destined to come back with me. For the past few days, I had been watching the Keys sunsets melt into the water with the same meandering mellow majesty that Hemingway must have witnessed, all that liquid gold rolling and blanching into the blue indifference of the waves.

Hemingway’s Cats, by Carlene Brennan and Ernest’s niece, Hilary Hemingway, is written with a style that could be accredited as “swooning.” Granted, there is a lot to admire about Mr. Hemingway. A medalled, devilishly handsome veteran, Hemingway became a celebrity at age 27 with the publication of The Sun Also Rises in 1926. He was manly, mysterious, and aloof, possibly a man who would never give his one-time friend, F. Scott Fitzgerald, credit for getting him published in the first place.

Connecting him with his own publishing house, Fitzgerald even edited Hemingway’s debut:

As Hemingway’s sponsor with Scribner’s, Fitzgerald had a considerable investment in the success of The Sun Also Rises. Upon his first read of Sun, Fitzgerald, a seasoned professional with a talent for revision, realized the book was not yet ready for publication. Fitzgerald’s critiques were delivered to Hemingway in the form of a ten-page handwritten letter that alternated between criticism and praise. He began the letter, “Nowadays when almost everyone is a genius, at least for a while, the temptation for the bogus to profit is no greater than the temptation for the good man to relax. This should frighten all of us into a lust for anything honest that people have to say about our work. Anyhow I think parts of Sun Also are careless [and] ineffectual. I find in you the same tendency to envelope in mere wordiness an anecdote or joke that casually appealed to you, that I find in myself in trying to preserve a piece of ‘fine writing.'”

It’s in Hemingway’s Cats that I learned how Hemingway at first feared that his own life would tarnish the perception of his work. As he wrote to his editor about the biography for the hardcover jacket of The Sun Also Rises (1926):

at once remove that biographical crap ie SHIT about me on the back wrapper…unless that material comes off all the wrappers immediately, and any reference to war service or my private life such as marriage etc removed, I will never publish another book with [the publisher].

Here, Hemingway shows a sensitivity to the distance we all know is both nonexistent and infinite: the space between an audience, art, and artist.

It was in 1939, just a few years after he had covered The Spanish Civil War, that Hemingway decided to move to Cuba and lead another kind of life.

A manly man?

No.

A macho cat dad.

A Feral Family

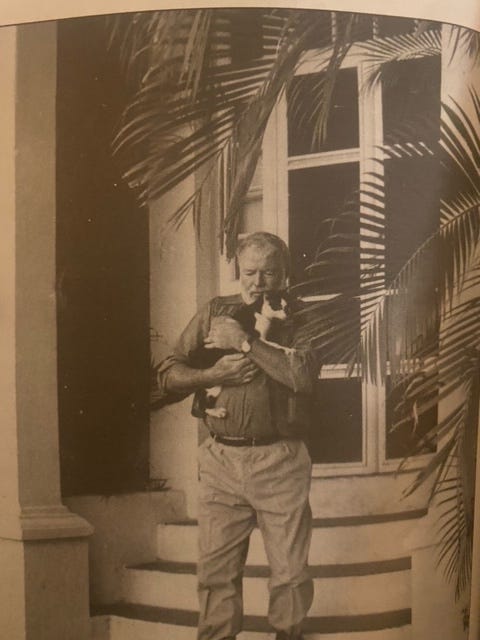

It’s in Cuba where Hemingway dedicates his mind to one thing: breeding the most powerful species of cat in existence. This flawless feline would be imbued with traits from what Hemingway identified as the three best cat breeds: a purebred Persian, a Cuban stray, and an Angora.

Really.

Hemingway’s Cats tells us that this macho cat dad mission started when he got a cat named Princessa. He admires her in a way that explicitly goes beyond cat dad. We see this in Islands in the Stream, a posthumous novel Hemingway began in 1950 that saw the light of day in 1970, nine years after his death:

Princessa was such a delicate and aristocratic cat, smoke gray, with golden eyes and beautiful manners, and such a great dignity that her periods of being in heat were like an introduction to, and an explanation and finally expression of all the scandals of royal houses. Since he had seen Princessa in heat, not the first tragic time, but after she was grown and beautiful, and so suddenly changed from all her dignity and poise into wantonness, Thomas Hudson knew he did not want to die without having made love to a princess as lovely as Princessa.

You read that right: Hemingway compares a cat’s heat to all the basest impulses that render empires to dust. Confronted with a half-crazy cat dad trying to breed a super cat in Cuba, Hemingway’s Cats showed me that I had read Hemingway’s work with a shallow understanding, simply because I hadn’t been able to read the artist himself.

A man fantasizing about a cat as royalty, hoping to start a Game of Thrones style brood, is lonely and depressed and tragic, seeking solace in serving the sublime. In other words, an artist.

Hemingway’s gratuitous displays of masculinity, his carefully curated collection of characteristics, are the signs of a man transmuting unnamable pain into the precious ornamental metals of power.

Nothing drives that point home more than when Hemingway finds a worthy “stud cat” for Princessa on Christmas morning:

An energetic kitten soon caught the attention of Hemingway. A Cuban kitten with unusual black and white markings was playing with its reflection on the glass cigar counter… It was Christmas morning and the bar was relatively quiet except for a few villagers who were still recuperating from the holiday parties the night before.

Alone at a bar on Christmas morning, Hemingway finds a cat he thinks is worthy of his princess cat. He’s already been married, and divorced. His children are somewhere else. He is alone, save for the glass in his hand.

Unfortunately for Hemingway’s super cats, his third wife, Martha snaps and has all the cats sterilized. One cat dies from complications.

As Hemingway’s Cats puts it:

When Ernest returned home and found out what his wife had done to the cats, he went into a violent rage. Martha had destroyed all his hopes of starting a new breed of cat with his purebred Persian Princessa and his adopted Cuban stray cat Boise and the Angora tiger cat Good Will. Hemingway never forgave his wife for her actions, telling friends that ‘she cut my cats.’

Even in his pets, Hemingway seems obsessed with preserving potency.

But for whose sake?

The Cat House

When Hemingway’s fourth wife, Martha, arrived at the Cuban estate, things had escalated further. As Hemingway’s Cats tells us:

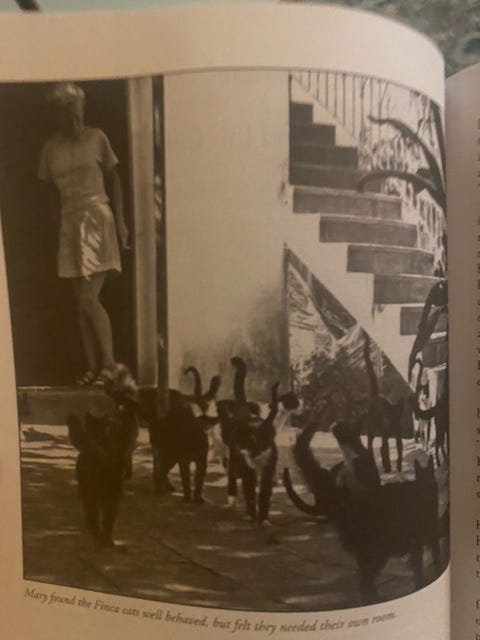

The cat family had the run of the house, sleeping in the guest bedroom on double beds. The room was situated in the center of the home, off the spacious living room, with a door opening to the back terrace, where the cats were… served ground meat, canned salmon, turtle meat when available, and fresh milk from the farm’s cows as well as treats of homegrown catnip when available.

Later, we’re told that the stud cats had a “terrible habit of spraying.”

As Hemingway’s sister, Madelaine, writes:

The bedroom between the living room and the veranda was the cat room. A couple of single beds and cushions were strewn about, as well as eating and drinking dishes to accommodate the scores of cats that kept accumulating. The room had a door that would swing in and out so the cats could come in and go at their pleasure, day or night.

Hemingway’s Cuban estate had become a full-time cat colony and he loved them all with a hoarder’s passion, no matter how dirty they made the home. It probably didn’t help that Hemingway liked to have three scotches before dinner and depended on two bottles of Claret almost every day. Cleaning up after cats is an alien nightmare to a hungover brain.

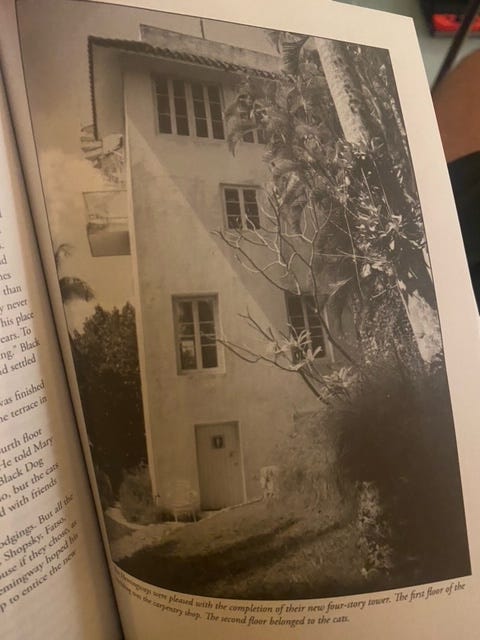

Martha decided it was time that the cat family moved to their own quarters. The resulting structure was more cat tower than cat house, rising four stories tall.

When alone, Hemingway wrote letters boasting that he had taught the cats how to drink whiskey and eat human food. He also told people he had taught them to climb on top of each other in acrobatc posese.

Were these real events made possible by the nature of unneutered cats and Hemingway’s steady supply of “homegrown” catnip? Or fantastical cat fiction written after a few bottles?

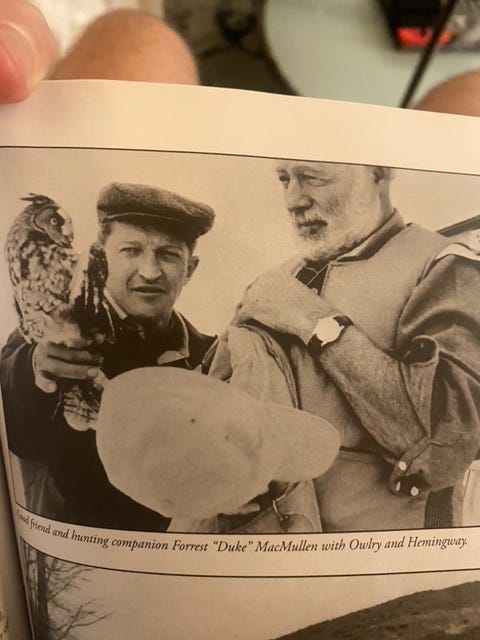

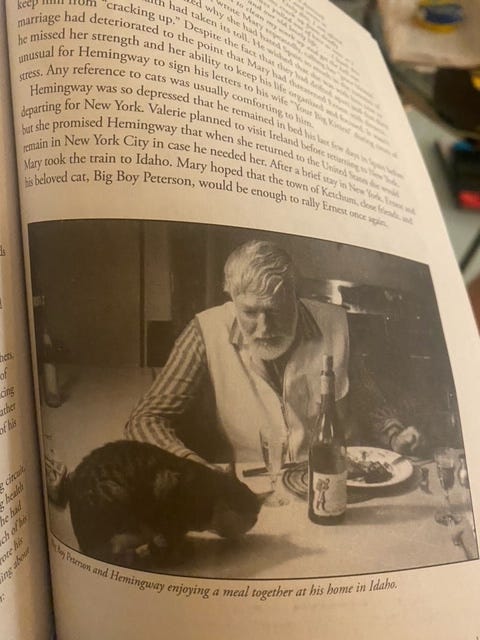

I vote for a little bit of both. This is a man who, later in life, had an owl as a pet who was so sad when he left that it flew after his car when he tried to leave the house. This is also a man pictured with cats and bottles in almost every domestic scene.

At the end of his life, Hemingway owned fifty-seven cats and twelve dogs. Hemingway’s Cats even tells us that, when he decided to take his own life after sessions of merciless and involuntary electroshock therapy, one of his favorite cats was by his side.

The Bold Belligerence of Insecurity

In his lifetime, Hemingway enjoyed fame and fawning for his lightning prose and wild adventures. But in modern assessments and modern adaptations of his personality - like the Ken Burns documentary - it’s very easy to not only abandon the artist, but to misinterpret the art.

Let’s go over the short list: after being mortared and machine gunned in 1918: Hemingway went to the Spanish Civil War in 1937. He went to World War II, where he got in trouble for trying to lead the troops as a journalist but, nonetheless, was awarded the Bronze Star. He hunted lions and elephants and fished for marlin that weighed hundreds of pounds. He was in back-to-back plane crashes in Uganda. In the second crash, he had to headbutt his way through the door and suffered burns all over his face.

Are we supposed to believe this real-life Captain America had the awareness, the depth to put any soul behind the head-butting of his prose?

The cats tell me yes. They tell me a story of a man lonely and lost. A man whose writing was powered by something other than the lust and love for adventure, and a writer whose every word held doors and mirrors behind it.

Hemingway is not a man to separate from his art, but, in a way, he’s an author whose persona initially spoiled the art for me by my own assumptions. I have regrets in the way I’ve read Hemingway. Visiting the books I remember as action-packed adventures, I find something deeper everywhere.

As we see in this passage, from For Whom The Bell Tolls (1940):

Dying was nothing and he had no picture of it nor fear of it in his mind. But living was a field of grain blowing in the wind on the side of a hill. Living was a hawk in the sky. Living was an earthen jar of water in the dust of the threshing with the grain flailed out and the chaff blowing. Living was a horse between your legs and a carbine under one leg and a hill and a valley and a stream with trees along it and the far side of the valley and the hills beyond.

I felt a deep guilt after finishing Hemingway’s Cats. I read him wrong, because I fell for the image Hemingway wrote for himself.

When you know too much about a creator’s personal life, the creation is compromised. That’s what happened with Hemingway. Which, if you remember, is what he feared most when The Sun Also Rises marked his debut onto the literary scene in the first place.

I owe Hemingway’s work another read. This is writing not from a he-man ready to take on the world, but a man who couldn’t help but care unconsciously behind the walls he built for himself, the defenses of a man so close to death in his youth that he only felt home back there, on the edge. And with his cats.

Hemingway, confusingly, was both merciless manly man and sensitive soul. But what better way to show the eternal tension of that truth than, beyond all other things, being a macho cat dad from start to finish?

The defense of Hemingway that I have always been looking for but never found until today. This was so great.

Lovely