YouTuber MrBeast (birth name Jimmy Donaldson) built a $50 million based on videos of extreme stunts, cash giveaways, and gaming. In his early twenties, he has more than 100 million subscribers. Earlier this month, 10,000 of those fans all arrived at a New Jersey mall to celebrate the opening of the first brick-and-mortar location of his restaurant chain, Beast Burger.

In a piece that describes him as a quiet kid who became obsessed with studying how to create viral content for YouTube’s algorithm, the journalist notes that Davidson’s reputation often precedes him.

His reputation for being cash-rich also comes with security concerns. His apartment was broken into three or four years ago while he was filming, prompting him to move to a gated community and into a house with bulletproof windows and triple-steel-reinforced doors. A bodyguard accompanies him whenever he ventures out in public in Greenville. These concerns do not seem unfounded: During our lunch at the Mexican restaurant, two teenagers wait outside in the parking lot for hours, and tail Donaldson’s car when we leave.

Donaldson acknowledges this is a problem of his own making. “I can create whatever world I want, do whatever I want for content, and I choose this,” he says. “[In] the end, I have tons of influence. If I wanted to, I could have tons of money. Boohoo, people have expectations of me. I’ll live.”

We live at a time when a single person can influence millions of people, often from the comfort of their own home. MrBeast is helped by the fact that he is known to reward his fans with money that can seemingly materialize at any point from thin air. In one case, a 20-year-old won $100,000 just for holding his finger on a MrBeast app button for more than two days straight.

From Kim Kardashian to MrBeast, Beyonce to the world of Instagram celebrities who can make or break brands and trends, becoming an “influencer” is recognized as a valid - and desirable - career path in an age where we all have one foot stuck in metaverse and one still stuck in the meatverse.

Estimates put the value of “social media influencers” at some $6.5 billion, which helps explain why one survey found that 86% of young Americans could see themselves aspiring to become an influencer and another found that becoming a “social media star” is the fourth most popular career aspiration for kids today.

The art and science of influence is a two-way street, and the influencers become just as influenced by their influence as everyone else, tirelessly creating new content, exploring new gimmicks to fortify the position of their own influence.

Last week, I explored how the mechanics of influence can backfire when, in the case of Kurt Cobain, the path to growth becomes an impossible task for an influencer dependent on their influence for validation and meaning.

This week, I want to look at how we can retroactively study the effects of Woodstock 1999 through a similar lens. And why, it’s obvious that Woodstock 1999, a widely understood disaster that ended all future Woodstocks, was, among so many other things, caused by influencer marketing.

Partying Like It’s 1999

Whether you’re watching HBOMax or Netflix’s Trainwreck (2022) or HBOMax’s Woodstock: Peace, Love, and Rage (2021), there is one scene from Woodstock 1999 used by both documentaries to establish the audience’s simmering rage at the world: the opening act of pop punk band The Offspring.

Menacing music plays. Lead singer Dexter Holland, possibly the least intimidating punk singer to walk the earth, opens the set wielding a cartoon bat and, one-by-one, decapitates five mannequins with the printed faces of each Backstreet Boys.

In both documentaries, humorless critics inform viewers that there was a population of turn-of-the-millennium America that did not, in fact, care for the Backstreet Boys. It’s implied that this is a fault of the audience, often characterized as a grumbling, lurching mass of malcontents frustrated with a changing world.

This skit, and the attitude of Woodstock 1999, are actually products of the same exact channel. Last week, digging into the void left behind by Kurt Cobain’s death, I learned that MTV’s countdown music show, “Total Request Live,” had been created as a way to churn out new influencers.

TRL gave us the legacy of modern music that still haunts radio waves today. For every episode, viewers voted on what songs deserved to be at the top of the charts. In 1999, this resulted in more than 200 days where The Backstreet Boys and NSYNC dominated the #1 spot.

But the show didn’t leave other viewers behind, instead featuring a performance of authenticity that explored a new kind of alienated rage through bands like Korn and Limp Bizkit, music purportedly made for those who felt dejected by the sudden popularity of boy bands and pop stars that, ironically, became popular through the exact same vehicle.

By pitting listeners of different genres against each other in a countdown format, it almost seems inevitable that, by the summer of 1999, there would be a backlash. We see that in the Offspring’s performance in both documentaries as one influencer (The Offspring) made popular by TRL literally pummels the influence of another (The Backstreet Boys).

The popular theory of Woodstock 1999 is that the bands were simply the wrong kind of influencers and the influenced were the wrong kind of fans. This is reinforced when, a few days later, the audience tears down equipment, sets fire to the venue, and starts robbing vendors.

The merciless choice of venue didn’t help. In the Netflix documentary, footage of the aftermath is described as a “refugee camp,” an apt description considering the site of Woodstock 1999 took place at Griffis Air Force Base, a 1940s military depot classified as a Superfund site in 1984 due to the lead, solvents, and other toxic chemicals buried in underground storage tanks that poisoned the local water supply for decades.

For three days, attendees were treated to a waterless desert of pavement hallucinating in triple-digit humidity and serviced by water stations that caused cases of “trench mouth.” Compared to the 600-acre dairy farm of the original Woodstock, this could only be described as some kind of hell.

One might say that the cynicism of the concert organizers of Woodstock 1999 matched the culture at the time, in which alienated consumers couldn’t defend themselves with outraged smartphone footage. All they had was the influence of their favorite bands as a way to achieve catharsis.

Strangely, both documentaries fail to mention that Woodstock 1999 took place at a Superfund site full of lead, a metal that bypasses the blood-brain barrier by mimicking calcium and is thought to be responsible for a surge of violence through the eighties due to the deteriorative effect it has on organs and behaviors, such as impulse control.

What we are at least given as a helpful way to shame attendees for their choice of music and their choice of reaction to it, however, is Woodstock 1969.

Peace, Love, and Vietnam

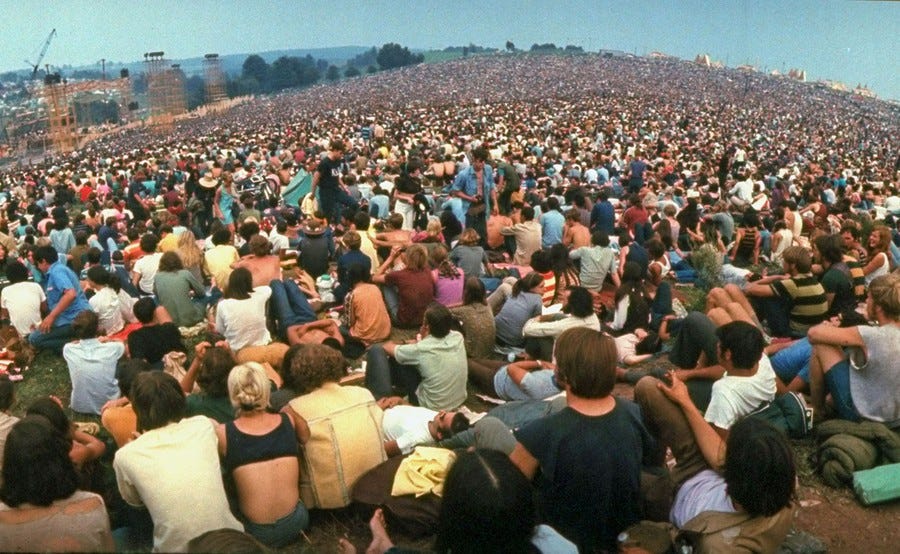

Woodstock 1969, which took place in Bethel, New York, from August 15-18, became a holy site of pilgrimage for half a million members of the hippie movement seeking the elemental transmutation of performance and authenticity.

People showed up in VW buses and put flowers in their hair. Jimi Hendrix played a famously mangled version of the “Star Spangled Banner.”

A look at the lineup shows an endless list of dreamy, LSD-friendly influencers of the music world, from Janis Joplin and Joan Baez to The Grateful Dead. This festival celebrated peace and love fueled by hallucinogens that helped people spiritualize hedonism and believe in the purity of peace or, at least, pacifism.

Woodstock 1969 is an endearing portrait of the Romantic Period of the United States, during which cultural memory will claim the poetries and protests of hippies solved all. Things may have been different if you were one of the 2.2 million American men drafted to the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1967, which amounted to about 8% of the 27 million eligible American males not headed to college and unable to get a medical deferment, the men who fell within the drafting age range of 18 to 26 destined for rehabilitation programs less competent than those found in many prisons and fated to generate a generation of children gifted a parent’s baggage to carry and call their own, those members of Generation X that would, thirty years later, find their own meaning at Woodstock 1999.

The differences of Woodstock 1969 and Woodstock 1999 are often painted as a moral failure of the audience. Why, the documentaries insistently seem to ask, weren’t the people listening to metal music at the waterless Superfund site thinking about peace and love?

It comes down to the influencers. Woodstock 1999 chose a line-up of heavy rock and metal bands as headliners. The answer can be a simple equation of sonic suggestion, rather than the deep cultural analysis that the documentaries attempt.

But if music is culture, then Woodstock 1999 does stand in stark contrast to Woodstock 1969.

In 1969, the influencers on stage created music to deny war.

In 1999, the influencers on stage created music to deny alienation.

In my mind, the difference in Woodstock 1999 is the crowd’s acceptance of danger and mortality through the embrace of darker music, an attitude that could be considered more honest than the fleeting fruitlessness of Woodstock 1969’s peace and love, considering two of the biggest acts (Joplin and Hendrix) died one year later from an overdose of peace and love and heroin and vomit at the age of 27.

The reason that Woodstock 1999’s beauty is hard to understand today is that danger and carelessness toward mortality are now seen as vices in of themselves, because the values of “toughness” have given way to safety and security. And that’s why it’s impossible for the narrators of the documentaries to even understand the crowd’s motivations as they take us through a few choice highlights of what, in their opinions, went wrong with the audience and the performances of authenticity.

This is clear from the first headliner of Woodstock 1999, nu metal sensation Korn, when they open with the song “Blind.”

In Trainwreck, lead singer of Korn, Jonathan Davis, recollects the fear he felt when going out to face the crowd of Woodstock ‘99. A man behind the scenes, he becomes an influencer on stage. He shows no fear. His performance moves people like a prophet parting seas.

This is how he gets hundreds of thousands of people to simultaneously chant:

You don’t know the chances

What if I should die?

On Saturday night, Day 2 of Woodstock 1999, there was only Limp Bizkit and, beyond Limp Bizkit, chaos. At least if we are to believe the documentaries, which fail to cover the acts that followed Limp Bizkit: Rage Against the Machine and Metallica.

These are mysterious omissions. Rage Against the Machine, following Limp Bizkit, set an American flag on fire. The next day, after potential cult leader, Woodstock founder, and artist-of-humanity Michael Lang decided to hand candles to the crowd and everything erupted in flames, we are treated to footage of Woodstock ‘99 in which a mob of kids set things on fire and rob vendors singing, “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me,” the refrain from Rage Against the Machine’s “Bulls on Parade.”

This is the only time the narrators deign to name Rage Against the Machine. Saturday night’s headliner Metallica isn’t mentioned in either documentary.

This leaves the documentaries to happily point the finger at the third-to-last band of the night, rap-rock outfit Limp Bizkit, when naming the band who destroyed Woodstock. This comfortably completes the thesis that Woodstock 1999’s doom was the ignorant resentment of a crowd that wanted to defy pop culture. Not people driven into a frenzy by an American flag burned to ash.

This is where TRL’s influence is front and center. Mid-set, rallying the crowd against the boy band NSYNC, Fred Durst asks the crowd if they’ve ever had a day when they want to break some shit. He proceeds to break into Limp Bizkit’s “Break Shit,” the millennium anthem of millions of middle schoolers everywhere, including myself.

Durst tells the crowd:

Time to reach deep down inside and take all that negative energy, all that negative energy, and let that shit out of your fuckin’ system.

The influenced jump and release at Durst’s command.

In Trainwreck, one observer claims that Fred Durst saw what was happening and kept going. What choice, though, does an influencer have when confronted with the infinite immersion of influence itself? You can see the wonder in Durst’s eyes. He knew he had created something beautiful in the performance of his authenticity.

Fred Durst called. Hundreds of thousands answered to perform the spectacle of self-actualization. Had the band really immolated the principles of Woodstock in the process? Had they violated a moral norm in spurring a crowd to commit to not peace and love but sweat and adrenaline?

The claim comes down to mechanics, not morality: the mechanics of influence.

Reach In, Reach Out

When we look at Kurt Cobain through a psychoanalytical lens, it’s clear that he became a captive to his own influence. TRL continued to mass produce new influencers to fill the void, as if capturing the fireflies of authenticity from each musical act and keeping them flickering in jars.

This is true for influencer, musician, writer, actor and painter alike: the work becomes the prison. Look no further than another TRL darling, Eminem, a rapper more comfortable spouting verses from the persona of Slim Shady and, who, jumping off a building in a music video for his song “The Way I Am,” chanted:

I am whatever you say I am.

Imprisoned by his own influence, Eminem raged against the confines of a persona that sustained and tortured him.

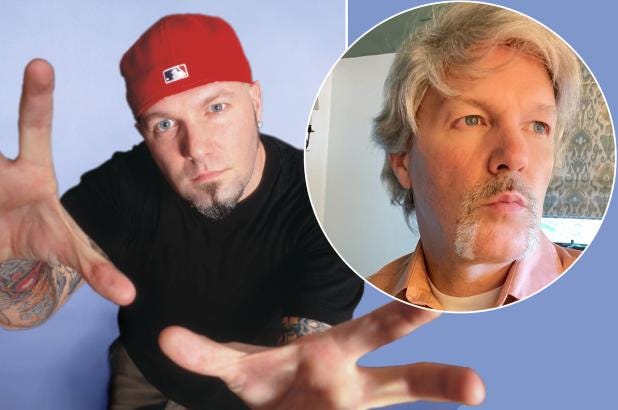

Blamed for what is shown to be the cataclysmic end of Woodstock, reviled in the musical world, a walking joke to the crowds who once adored him, Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst, too, became morose over the years, a man who fell to earth due to the gravity of his own persona.

As he explained it in an interview:

I always knew the guy in the red cap was not me. I'm Dr Frankenstein and that's my creature. Being a breakdancer, a graffiti artist, a tattoo artist and liking rock and hip hop was too much; it was a conscious effort to create Fred Durst and eventually I had to bring that guy out more than I wanted to. It took a life of its own. I had to check into that character – the gorilla, the thing, the red cap guy. It's a painful transformation, but I do it 'cos that's what I was taught to do when you have people pulling at you.

Are we to judge an artist for the impact of a persona’s performance?

No one ever knows.

On July 29, 2021, a mere six days after the premiere of HBOMax’s documentary, Durst purged his Instagram and debuted a new face that was captured with incredulity by social media and the occasional celebrity gossip website.

The fact that Durst is blamed for so much of what went wrong with Woodstock 1999 is a testament to his influence. No one can possibly believe Durst may be a reflective human being capable of genuine growth, because his performance of authenticity, as an agent of the id, is so convincing. Today, he’s acting in movies.

Influencers are performers. This is as true as it is for the musicians of Woodstock as it is for YouTubers like MrBeast. As one friend put it:

“If you ask anybody that knew Jimmy before, they’d be like, ‘Really? Jimmy got famous?’ He was always real quiet.”

In the earth-shatteringly grand performances of Woodstock 1999 now streaming on so many channels, forever, we see a feedback loop between artist, work, influence, and influenced so pure, so powerful, that it is inscrutable to the observers today, because the moment has passed.

The influence, sadly, has become obsolete. The influenced have moved on. But, when we see these documentaries and relieve these moments, we refuse to let the influencers move on from the work. Instead choosing to chain the artists, permanently, to the work.

Still carrying that old dead soul on his shoulders, Fred Durst is crossing the Acheron, in search of the limbo he knows as paradise, still a golem swatting the hammers that shape him against his will, only to realize, looking down at his hands, that, just like Kurt Cobain and Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison and Janis Joplin and Amy Winehouse, he has held the hammers all along.

Yet the stars that survive their influence and become something else are an interesting case study in perpetual growth, and the long, endless road that self-actualization could be said to require.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow would explain it this way:

We fear our highest possibility as well as our lowest ones. We are generally afraid to become that which we can glimpse in our most perfect moments… We enjoy and even thrill to the godlike possibilities we see in ourselves in such peak moments. And yet we simultaneously shiver with weakness, awe and fear before these very same possibilities.

Unlearning the fear of our highest potential is one thing. Understanding that the process becomes our persona is another.

Staring into the wistful blue eyes of an unfamiliar Fred Durst, I can’t help but think reaching the highest level of our potential is a dangerous state, because it is always temporary, which can be disappointing, and, one way or the other, it haunts us afterwards. The real trick is to make sure that we aren’t the ghost.

Had no idea about the Superfund detail: I knew it was shoddily planned, but Christ. And ditto Drew's thoughts at your Great Prose in transforming good ol' Fred into a figure of myth and allegory 🫡

In light of all the catastrophically stupid and cynical planning decisions made, it's hard to envision how things could've played out differently. It's also much easier than I thought to interpret the kids' actions as a principled stand against forces of alienation. As ever, the bond between influencer and influenced takes on dimensions entirely of it's own; Woodstock '99 shows the perils of having gatekeepers ignorant of what the nature of those bonds when bookings were made. Who the hell assembles that Saturday lineup and says, "Peace and love, amiright??"

Great piece. Influence is fascinating, and your take on it is illuminating. The line about golems swatting away the hammers that shape them...🤯