When we think of Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (1896-1940), it’s inevitable to think of the glorious Jazz Age of New York he portrayed in The Great Gatsby. If we’ve seen the movie, we may hear Jay-Z and throbbing bass or see Toby Maguire staring wide-eyed out a window. You may even recall the meme of Leonardo DiCaprio that immortalized Fitzgerald’s work in ways he would have never thought possible.

Like any good New Yorker, Fitzgerald spent his final years in Los Angeles. The Last Tycoon, the novel he left unfinished, was not about the magical thinking of New York City but the silver screen dreams of Hollywood. According to literary critic Edmund Wilson, the novel is Fitzgerald’s most “mature” work and, even after reading the half of the novel that does exist, most readers would likely agree. The Last Tycoon offers a timeless perspective on the mechanics of movies and, consequently, the mechanics of dreams.

How did Fitzgerald end up in Los Angeles in the first place? Blame the Great Depression. And his depression. His first two novels, This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Beautiful and the Damned (1922), made Fitzgerald a household name and unlocked a potential that turned to poison, as we covered last week in Litverse. The rest of the his novels, including The Great Gatsby (1925), were commercial failures and never achieved success in Fitzgerald’s lifetime. Broke, desperate, and recovering from a nervous breakdown, while spending most of his money on his estranged wife Zelda’s psychiatric treatment and his daughter’s education, it was in 1937 that Fitzgerald headed west in search of a second act and ended up living at a place called the Garden of Allah.

To Catch a Falling Star

Dear Scott,

I don’t know where you are living and I’ll be damned if I believe anyone lives in a place called ‘The Garden of Allah,’

-Thomas Wolfe, Letter to Fitzgerald (1937)

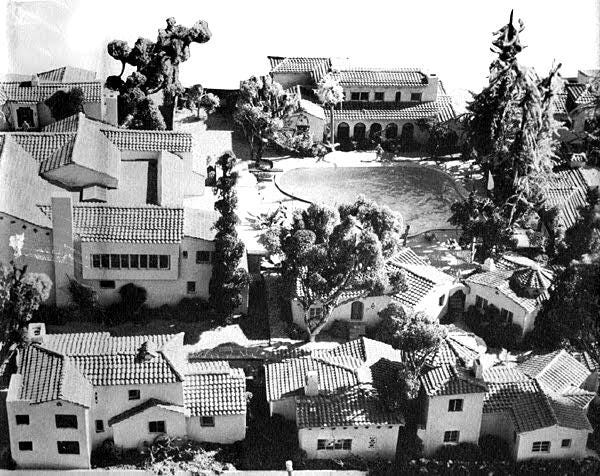

Fitzgerald’s career as a screenwriter started with a contract from MGM in 1937. Aged 41, he moved into a “bungalow colony” for screenwriters on Sunset Boulevard named The Garden of Allah. For a writer who Gertrude Stein, infamous ringleader of the Paris salons, had called superior to Ernest Hemingway, who Edith Wharton herself had admired, the final resting place of Hollywood must have seemed a cosmic mistake. But his fall westwards had been slow and steady, then all at once.

We can see the disassociation in a letter Fitzgerald wrote to himself when he arrived at his new home:

Dear Scott —

How are you? Have been meaning to come in and see you. I have living [sic] at the Garden of Allah.

Yours, Scott Fitzgerald.

The common consensus is that Fitzgerald “failed” as a screenwriter. Director Billy Wilder (1906-2002), who reigned in Hollywood for five decades, described the mismatch in cinematic terms: Hiring Fitzgerald as a screenwriter was like hiring “a great sculptor… to do a plumbing job.”

What’s apparent in the tales of Fitzgerald’s screenwriting career - which only lasted the three years from 1937 to his death in 1940 - is that he couldn’t stand the Hollywood model of writing by committee. It wasn’t the product that mattered, he decided, it was the process. That’s where he found the inspiration for The Last Tycoon.

The Silver Dream

“There’s nothing that worries me in the novel, nothing that seems uncertain. Unlike Tender is the Night, it is not the story of deterioration- it is not depressing [or] morbid in spite of the tragic ending. If one book could ever be ‘like’ another, it is most ‘like’ The Great Gatsby than any other of my books.”

-F. Scott Fitzgerald on The Last Tycoon

If The Great Gatsby is a dream of status, The Last Tycoon is about how dreams are made. Most of the reader’s time is spent with protagonist Monroe Stahr, a producer with a miracle’s touch to make real, or at least profitable, any dream by committee. In poeticizing production, The Last Tycoon illustrates the industrial scale of the movie industry and explores how most of Hollywood’s silver screen dreams are assembled piece-by-piece and manufactured into a product rather than summoned into being by the pure intention of production and brilliant acting. We see this in action when Stahr commands, one after the other, transformational changes to scenes, dialogue and plot points or suggests new camera angles or even new actors and directors. These commands are dictated with no opportunity for disagreement. The committee presents each possibility as if every scene is an individual lump of clay and Stahr breathes life into it by divine right, as if an oracle. As Fitzgerald describes the process of the screening room in the novel:

The oracle had spoken. These was nothing to question or argue. Stahr must be right always, not most of the time, but always - or the structure would melt down like gradual butter…

Another hour passed. Dreams hung in fragments at the far end of the room, suffered analysis, passed - to be dreamed in crowds, or else discarded.

Let’s linger on that final phrase: every film is to be interpreted here as something that can only be “dreamed in crowds” or discarded, making all mass dreams dependent on what the producer decides when creating one dream from many, as if a tapestry. The factory floor is full of ideas, half-assembled. The Last Tycoon shines with warm admiration and sympathy for producer Monroe Stahr, even when he’s the operator pulling the levers in this industry of immersion. We see this clearly when Prince Agge of Denmark, getting a tour from Stahr and observing a playwright couple, asks how screenwriters are qualified. Stahr responds that, in choosing writers, he will choose:

“Anybody that’ll accept the system and stay decently sober - we have all sorts of people - disappointed poets, one-hit playwrights - college girls - we put them on an idea in pairs, and if it slows down, we put two more writers working behind them. I’ve had as many as three pairs working independently on the same idea.”

“Do they like that?”

“Not if they know about it. They’re not geniuses - none of them could make as much any other way. But these Tarletons are a husband and wife team from the East — pretty good playwrights. They’ve just found out they’re not alone on the story and it shocks them - shocks their sense of unity - that’s the word they’ll use.”

“But what does make the - the unity?”

Stahr hesitated- his face was grim except that his eyes twinkled.

“I’m the unity,” he said.

In Hollywood, all ideas are nothing but screws on cogs to be adjusted, calibrated, removed or replaced. At times, The Last Tycoon lurches for direction, a zombie animated with dead magic exposing a leaky belly of unfinished life, but the half-novel is interesting enough to justify a read. Various chapters are narrated in the first-person by Cecilia Brady, the daughter of a famous producer, while others are narrated in the third-person to tell the story of Stahr’s quest to woo the elusive Kathleen Moore, an Irish woman who bears an uncanny resemblance to Stahr’s late wife, an actress by the name of Minha Davis.

What does Stahr want from the romance? He wants to become new by forgetting himself. We see this when Moore asks what he wants from her:

“Be a trollop,” he thought. He wanted the pattern of his life broken. If he was going to die soon, like the two doctors said, he wanted to stop being Stahr for awhile and hunt for love like men who had no gifts to give, like young nameless men who looked along the streets in the dark.

He wanted the pattern of his life broken. It is in these natural sentences, the ones where each word is a mountain, that we see glimpses of a writer who had decades ahead of him and some number of masterpieces yet left to create. As always, Fitzgerald shows in The Last Tycoon the traitorously transpicuous life of dreams and the gossamer promises they represent, sparkling with the brilliance of a cobweb in sunlight. As Stahr observes Kathleen, trying to superimpose his wife onto her to make himself feel something, but something new, Fitzgerald represents how our lives become one with what we see, whether alive or dead, real or imagined, physical or virtual:

He watched her move, intently, yet half afraid that her body would fail somewhere and break the spell. He had watched women in screen tests and seen their beauty vanish second by second, as if a lovely statue had begun to walk with the meagre joints of a paper doll. The fragility should be an illusion.

Stahr, with all the tact of a contestant on Love is Blind, tells Kathleen when comparing her to his wife:

“You look more like she actually looked than how she was on the screen.”

This is a powerful meditation on the life we expect when the silver screens of dreams become backdrops for how we understand being. Even reflecting on the memory of his wife, Stahr’s memory is not her but the characters and personalities and dreams she represented in movies. Because what else is left for him to remember Minna Davis, his late wife, than the trail of diamond dream dust she left behind on the silver screen?

The Last Tycoon shows how Hollywood shapes our dreams and how those shapes are crafted, clay-like, by committee. Fitzgerald witnessed the birth of Hollywood in a way one might witness the birth of a rainbow. The novel is a joy to read, because there is so much familiar genius and sensibility in the lyrical prose, but now that distinct Fitzgeraldean prose is paired with the precise elegance of themes that bloom beneath the surface. For example: The novel starts with Cecilia flying from New York City back to Los Angeles, but the flight makes an emergency landing in Nashville. Along with a studio writer and a producer, she takes the opportunity to visit Andrew Jackson’s estate. The site is closed when they get there, so all they can do is see it from afar. The producer, who has been disgraced in his career, decides to stay behind. Landing in Los Angeles the next day without him, Cecilia hears that he committed suicide there.

An unfinished novel in our hands, we are left to wonder at the intended association between President Jackson and Hollywood’s failed dreams. Other than his assertion that The Last Tycoon is thematically resonant with The Great Gatsby, we only have Fitzgerald’s notes to for further our understanding of this missing novel. This is where we can identify the maturity that Edmund Wilson claims is on full display, because Fitzgerald is now careful not to overwrite, noting:

“I cannot be too careful not to rub this in or give it the substance or feeling of a moral tale…If the reader misses it, let it go- don’t repeat.”

The Last Tycoon leaves us with a vision beyond the vision: the production of feeling in a society where seeing is believing and believing is a feeling. As Prince Agge reflects during a tour of a studio set:

From a little distance they were men who lived and walked a hundred years ago, and Prince Agge wondered how he and the men of his time would look as extras in some future costume picture.

Then he saw Abraham Lincoln, and his whole feeling suddenly changed... He had been told Lincoln was a great man whom he should admire, and he hated him instead, because he was forced upon him. But now seeing him sitting here, his legs crossed, his idly face fixed on a forty-cent dinner, including dessert, his shawl wrapped around him as if to protect himself from the erratic air-cooling- now Prince Agge, who was in America at least, stared as tourist at the mummy of Lenin in the Kremlin. This, then, was Lincoln. Stahr had walked on far ahead of time, turned waiting for him- but still Agge stared.

This, then, he thought, was what they all meant to be.

As easily as dreams are delivered, of course, they are even more easily dissolved. Fitzgerald finishes this revelation with what may be one of his funniest lines:

Lincoln suddenly raised a triangle of pie and jammed in his mouth and, a little frightened, Prince Agge hurried to join Stahr.

Is there any significance between a suicide at President Jackon’s estate at the beginning of The Last Tycoon and the fake Lincoln gorging himself on pie in front of a Lincoln-hating Danish prince who is about to be engulfed in World War II but suddenly believes in the American Dream after seeing how the dream dreams of itself? Are we to assume Fitzgerald is comparing President Jackson’s Indian Removal Act and the subsequent Trail of Tears to the doomed journey of so many hopeful generations to the west, seeking a second act, and the caricature of President Lincoln acting as an extra on a movie set as a satirical symbol for unity? We might be accused of reading too much into it.

In The Last Tycoon, Fitzgerald explores one thing above all: the price point of a dream. In the studios, he gets to the raw numbers - a very real portrayal that Joan Didion elaborates on in Hollywood: Having Fun (1973) when she analyzes how the thrill for Hollywood insiders comes not from the motion of moving pictures, but the momentum of the deals that move the movement. Fitzgerald was the first writer to so eloquently bring the production of dreams to life behind the scenes. Did he find a new truth? It’s hard to say, but the notes left behind from The Last Tycoon make one thing clear in a note he wrote to himself: “There are no second acts in American lives.”

Come back next Monday (12/26) to read about Joan Didion’s committee calculus of Hollywood, and how she felt about Fitzgerald final novel three decades later. Want to read about the arc of Fitzgerald’s career? Read F. Scott Fitzgerald and the Poison of Potential.

Thank you for writing this, and the post before. As a reader it is one of my ultimate frustrations that we never got to read the finished version of The Last Tycoon, but perhaps him completing such a mature work would have undone the meaning of the longer real life work he was the protagonist of, ‘The Life of F Scott Fitzgerald’. So much of his life expresses an idea of America - beautiful, glamorous, ungraspable and ultimately ruinous for those who reach for it - that for him to have lived out his days in a second act as a clean former alcoholic writing great fiction in LA might have somehow robbed us of the intertextual Uber Novel he was living and the meanings we’re all still reading into it. I don’t want art to break all of the people who make it, but somehow his life and the way it played out has a meaning that sits as a counterpoint and compliment to his fiction. We’re still trying to fill the silences left by his voice and way of seeing, and suspect because of this unfinished work we always will be.