Am I just putting myself in a position where, in four years’ time, I’m going to be earning significantly less money than people I went to school with?

-Sazi Bongwe, Harvard freshman

The recent New Yorker article “The End of the English Major” first came to my attention on Twitter. The responses rapidly rallied to deny the thesis, but The New Yorker presents compelling numbers to back up the clickbait:

From 2012 to 2020:

Tufts lost ~50% of humanities majors

Boston University lost 42% of humanities majors

Notre Dame lost 50% of humanities majors

The study of English and history at the college-level dropped by 33%

More than 60% of Harvard’s class of 2020 planned to enter tech, finance, and consulting jobs

It’s an anonymous interview subject, a “late-stage career English professor,” who drives a stake in the heart of the humanities when he tells author Nathan Heller:

The age of Anglophilia is over… I don’t think reading novels is now the only way to have a broad experience of the varieties of human nature or the ethical problems that people face.

It is this assumption - that the study of novels must necessarily offer a solution to a problem and not just a process with its own rewards - that has effectively ended the English Major. Blame Gen Z. Just like previous generations of college students, they want to make a difference. This time around, though, paying tens of thousands of dollars to be taught how to interpret books is seen as a hobby with no attributable outcome, not a career. College, an investment, must produce capital and careers are where one finds that capital. Capital is power and power propels purpose.

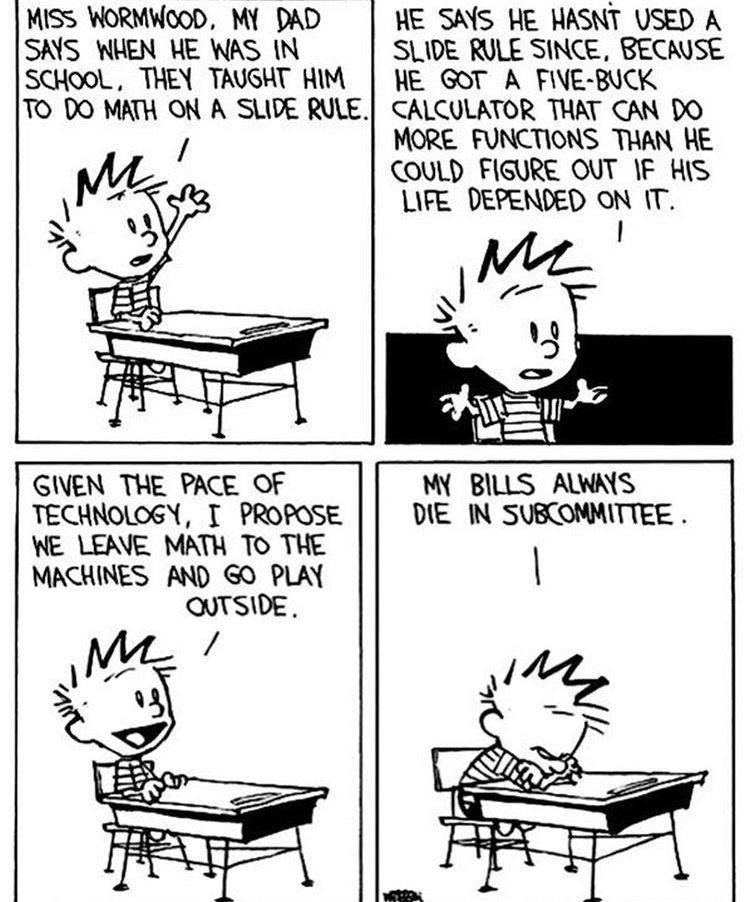

In this new understanding of humanities, passion is privilege and numbers are the truth. As Heller notes, one of the most popular classes at Harvard is now introductory statistics: enrollment rose from 90 students in 2005 to 700+ today. If my math is correct, that marks a 677.78% increase. Wow, what a graph.

The English Major is dead. Long live statistics, which can not err.

Masters of Anti-Mastery

To form a basis for the failure of the humanities, one can turn to French philosopher and politician Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859), who, at age 26, visited the the United States of America for nine months in 1831 and produced two volumes of Democracy in America (1835, 1840).

Tocqueville, an aristocrat’s aristocrat whose great-grandfather was guillotined, analyzes democracy in muted wonder and notes that when everyone is equal, expertise is seen as both a threat and a new form of bondage. Americans are uncomfortable accepting any critic’s interpretation of events as superior to their own. This problem has only gotten worse as the internet has unlocked infinite interpretations. Americans don’t want to wrestle with nuance. We want to get to the conclusion, because we have careers to attend.

As Tocqueville notes:

Equality extends to some degree to intelligence itself. I do not think that there is a single country in the world where, in proportion to the population, there are so few ignorant and, at the same time, so few educated individuals as in America…. Almost all Americans enjoy a life of comfort and can, therefore, obtain the first elements of human knowledge. In America there are few rich people; therefore, all Americans have to learn the skills of a profession which demands a period of apprenticeship. Thus America can devote to general learning only the early years of life. At fifteen, they begin a career; their education ends most often when ours begins. If education is pursued beyond that point, it is directed only towards specialist subjects with a profitable return in mind. Science is studied as if it were a job and only those branches are taken up which have a recognized and immediate usefulness.

In much of Democracy in America, Tocqueville contends with his admiration for the American experiment and a concern that pure capitalism could lead to a stunted intellectual culture. If everyone can get an education, but the purpose of the education must be profit, who will be left to create odes of wonder and philosophies of the soul?

If we’re to believe Heller, students now take it for granted that all literature and the value of literature and the currency it provides is seen to be subjective and therefore objectively useless. No one can be the expert, because to be an expert is to contradict someone else’s lived experience of a work of art. Critics are offensive and erudition is obsolete. Students love statistics class because it is numbers they want to prove the reality they believe, not stories. It was the outbreak of COVID-19 when it became just how clear culture ceded control to the science of data and the worship of charts as royalty. Who can resist a truth when it is studded with the gems of numbers or presented with a blood-red line chart? Stories only mattered if they started with statistics.

In 2020, the adjustable chart became truth. Stories that contradicted the charts were shunned, ignored, or called into question. Numbers became feeling. Forecasts became virtue. Spreadsheets became our constitution.

Think for Yourself, Question Authority

The cannibalism of counter-culture devours old institutions and replaces them with new ones, but only if the revolutionaries agree on their new values. This is where Gen Z, more so than any other generation, may be stagnating: agreeing on what’s right in a statistically subjective world. “Vibes” is now the measurable unit for cultural critiques. One literature professor at Harvard, who Heller identifies as “not old or white or male,” explains that students have an instinct to label something “problematic” if they disagree with it but they don’t actually engage with the material beneath the judgement.

As Heller summarizes this unidentified professor’s viewpoint:

[Students] seemed to have found that merely naming concerns had more value, in today’s cultural marketplace, than curiosity about what underlay them.

In this approach, literature is not so much an experience in college, it is a machine destined for decoding. Heller proffers an example regarding Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814):

Once, in college, you might have studied Mansfield Park by looking closely at its form, references, style, and special marks of authorial genius… Now you might write a paper about how the text enacts a tension by both constructing and subtly undermining the imperial patriarchy through its description of landscape. What does this have to do with how most humans read?

The implication here is that contemporary literature classes focus don’t focus on how old books connect us to stories our shared humanity, but how old books maliciously overlooked specific stories of said humanity. Every author and literary work is guilty of ignorance and ignorance is irrelevance when awareness is currency. Jeffrey Cohen, dean of humanities at Arizona State University, is keen to get hip with the kids. As he describes his philosophy of adaptation:

Instead of a teacher telling you why it might be relevant, but there doesn’t seem to be any connection to your lived experience, I think it’s important to have every model of learning available.

These futuristic models of learning, one might assume, are built upon an acceptance that no teacher has the right to be an expert on a subject or inflict their opinions on their class, therefore giving us a wholly new and useless definition of the word “teacher.” After all, if every personal understanding of the material is equally meaningful and valid, what is left to be taught?

Amanda Claybaugh, Harvard’s dean of undergraduate education, presents a simpler hypothesis: college kids can’t read.

Young people are very, very concerned about the ethics of representation, of cultural interaction—all these kinds of things that, actually, we think about a lot… The last time I taught ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ I discovered that my students were really struggling to understand the sentences as sentences—like, having trouble identifying the subject and the verb… Their capacities are different, and the nineteenth century is a long time ago.

Progress and Purpose

One in three college students have used AI to write essays, which proves that writing and reading, impossible-to-quantify processes, are treated with the same respect as electives or yoga classes.

Who can blame the students? They grew up in the shadow of the recession. They know college debt is a boulder to be carried uphill. It is skills that sustain us, not stories. The determination to follow an educational career charted to the merciless maximum of statistical probability of immediate return on investment is admirable and understandable. It is also wasteful. For a generation so attuned to culture, there seems to be an overlooked fact that it is not necessarily the English major, but all majors, that are going to become passion projects in the new economy. From fashion influencers to Mr. Beast, it is obvious that, upon graduation, it will be your portfolio, your record of creation, that matters most.

What we might be missing, perhaps, is a hustle culture for the humanities, a celebrity or self-actualization guru with a Tony Robbins aura or the precise purposes of Oprah or the rousing muzak of “Shark Tank” to prove that the humanities, in teaching you how to understand the world and how things work in principle, not practice, are as good for a future career as a knowledge of how computers or numbers talk. Because machines, for all their power, are only given meaning through the stories we tell each other about the conditions of their calculations. Where is our legion of influencers offering Instagram Reels and TikToks of literary criticism?

English majors, humanities majors, should unite in the passion for a subject that has never been socially sanctified as having a meaning outside of itself. But this time it is up to us to not only experience the literature, but create our own magic from that literature. Because no matter what you do, it is what you create that creates your life and your career and what we create has a value that needs no validation.

I'm Gen-Z (somewhat, graduated 2019) and majored in both Statistics and English so this is a fun piece for me.

I truly believe in the power and importance of the English major, but I'm employed because of my Statistics major, and it's nice to be employed. Statistics classes aren't directly relevant to what I do at work, but it proved that I knew how to move numbers around a spreadsheet. The English major is relevant to what I do on Substack, but I do this for fun not for employment. I view my English degree as a nice hobby I got to indulge for a few years in college with really talented professors who taught me a lot about art. Many people who don't do an English major see it the same way.

I also don't think there's anything wrong with that though. Art doesn't provide the same strict utility as the cold numbers can, and that's fine. What's sad and scary is that the standards of the English major decline alongside its relevance.

I’m gen z (19 and in college) and I think the cause and effect here are a little backwards. We don’t see English as formulaic essay-production where you connect old texts to Current Politics and our Personal Issues just cause. That’s how we (or at least I) are taught. Essay writing in high school (and as I hear from a friend, community college) is not at all “impossible to quantify”! Write this many words, in this format, on this question. Hook, intro. Body, body, body. In conclusion. Not all of my English teachers wanted that, but those others were often perfectly happy with progressive politics in a certain tone. Getting good grades and “very insightful!” responses to vague nonsense lowers one’s opinion of the whole game for attentive students. Generative AI (which I wrote my English paper final on months before people started going crazy on twitter and really disturbed by English prof) writes at about the level a lot of us write at, or better. I’ve also taken playwriting classes, which were very different than analysis-type classes but I violently hated and don’t remember them well, so I can’t talk much about fiction writing.

I also think the stats increase is more response than effect wrt the relentless graphs. We’ve grown up with numbers and averages and graph bombardment, and need to know how to read them. They are stories, with viewpoints and messages and omissions, and understanding that is crucial to anyone trying to engage with modern life.

It’s also true Youths can’t/don’t read much longform, dense text. I do, but I’ve been weird for that all my life. On the other hand, we’re processing information at incredible rates, all the time (email, text, ads, headlines, podcasts, yt videos, twitter, insta, etc.). There just isn’t much space left for Brothers Karamazov.

[edit: minor grammar fixes]