But men labor under a mistake. The better part of the man is soon ploughed into the soil for compost. By a seeming fate, commonly called necessity, they are employed… It is a fool’s life, as they will find when they get to the end of it, if not before.

-Henry David Thoreau

I spent a month trying to write this essay. There have been rewrites, edits, cuts, slices. Cross-sections. A writer’s block that ChatGPT could never prompt. I almost abandoned the whole thing. Who wants to write about the economy? Who wants to learn anything about economics in any way?

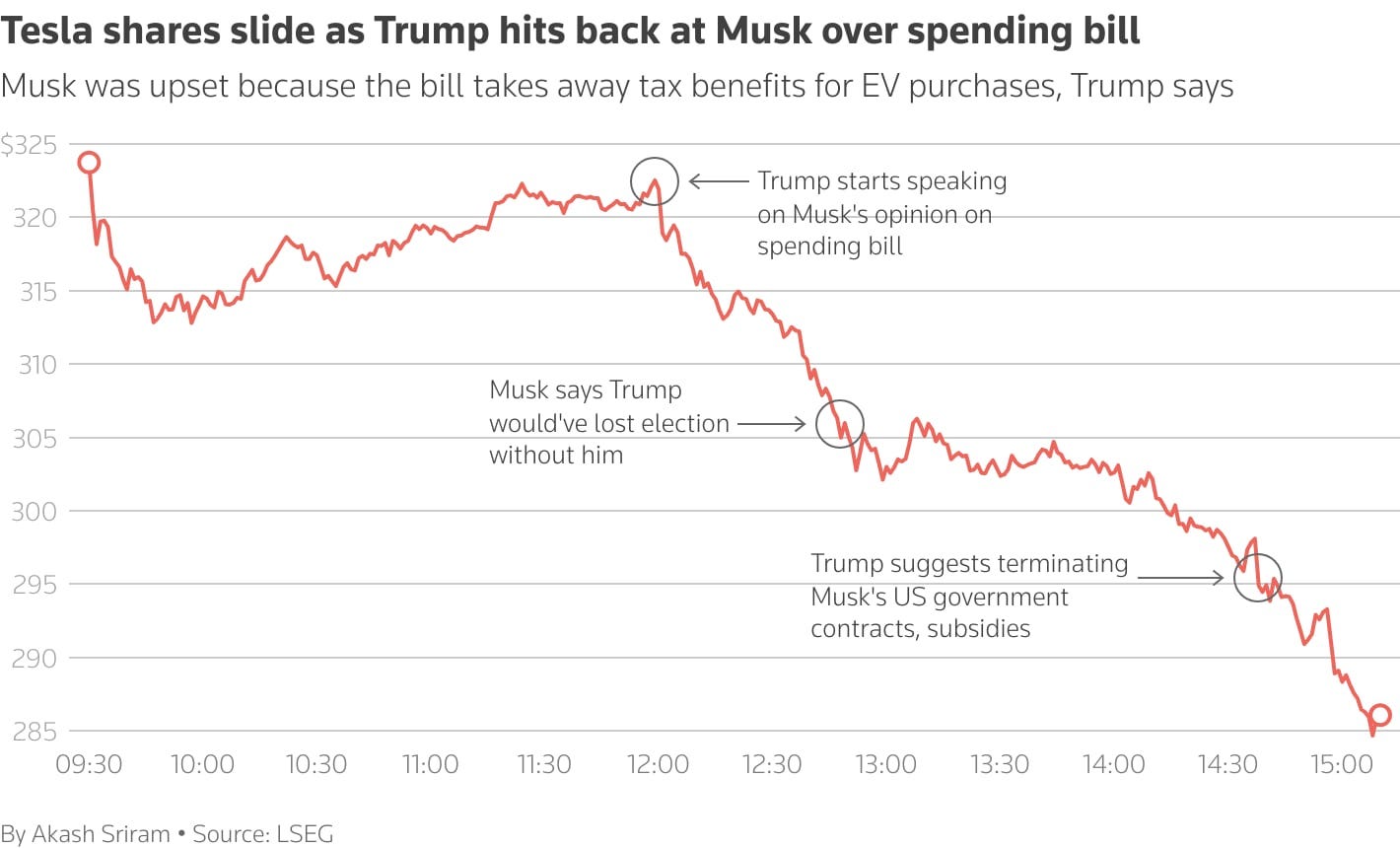

I kept coming back, because I feel like we’ve all arrived at the same inevitable conclusion: the modern economy is made up. Things stopped making sense a long time ago. There’s no point in trying to understand why or how things happen in the economy. The market is not magic. The market is madness. Just look at what happened to Tesla’s stock when Elon Musk started to insult Donald Trump.

We have obviously gone from a fun made-up magic economy to a desperate and pathetic madness economy. Three other examples from this year:

The Trump administration announced international tariffs on Liberation Day and everyone claimed the rules had been written by ChatGPT

I asked my friend in crypto what to buy and he recommended a coin called “DICKBUTT”

Trump got asked about the “TACO” wisdom of Wall Street: “Trump Always Chickens Out”

The economy is made up.

But how? But why?

In 1958, Harvard economist John Galbraith tried to explain.

From Scarcity to Surplus

John Kenneth Galbraith (1908-2006) had a writing career that was only outshined by his political career. He wrote nearly fifty books and more than a thousand essays. In 1946, he received the World War II Medal of Freedom. In 2000, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He served in the Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations. He also taught at Harvard. Galbraith had little that could stand in his way. Literally. At six feet, nine inches, he may have been the tallest economist-writer-politician to ever live.

Galbraith believed that, ever since World War II, we’ve gotten economics all wrong. Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus came up with a central tradition of economics while living during the eighteenth and nineteenth century. It was a time of plagues, famine, drought, suffering and scarcity. Their understanding of the economy - and every theory that came after - is based on a world where poverty was the expectation and the rule.

After World War II, the US became affluent. In an affluent society, supply and demand is less about food and shelter and more about production for production’s sake. Since we measure the GDP by production, production is how we measure society’s well-being. An economy that isn’t growing is dying. Policy, people, and products are centered on the idea of producing more, faster, better.

John Galbraith breaks this down in 1958’s The Affluent Society.

In the grim world of Ricardo and Malthus, the ordinary citizen could have no interest in social security in the modern sense. If a man’s wage is barely sufficient for existence, he does not worry much about the greater suffering of unemployment…

Men who are engaged in a daily struggle for survival do not think of old age, for they do not expect to see it.

You would think, as fewer people feel the threat of starvation or exposure, we would calm down and relax. But slowing production means slowing profits. Slowing profits means slowing markets. Slowing markets means unemployment. Everyone becomes married to the market. The market becomes married to our minds.

In the poverty-first economic theory before World War II, it wasn’t hard for people to figure out what they wanted:

The poor man has always a precise view of his problem and its remedy; he hasn’t enough and he needs more.

In an affluent society, desires are created and simulated so production keeps going:

When man has satisfied his physical needs, then psychologically grounded desires take over… these can never be satisfied.

Who can say for sure that the deprivation which afflicts him with hunger is more painful than the deprivation which afflicts him with the envy of his neighbor’s new car? In the time that has passed since he was poor his soul may have become subject to anew and deeper searing.

Suffering, humanity, and reality are all measured on a sliding scale.

In an affluent society, scarcity isn’t the enemy. Stagnation is the enemy.

More die in the United States of too much food than too little. Where the population was once thought to press on the food supply, now the food supply presses relentlessly on the population.

Production is the ultimate signal of health for the national economy and the country, and for every company and every citizen. As Galbraith explains:

It is an index of the prestige of production in our national attitudes that it is identified with the sensible and practical. And no greater compliment can be paid to the forthright intelligence of any businessman than to say that he understands production.

How can we make sure that production keeps going? Maximize profits, minimize risks. And keep making sure that everyone knows that perpetual production is important and urgent and necessary. From gamifying relationships to fast fashion, fast food to AI, it’s inevitable that maximum production with minimal risk produces slop. The slop that we need the least. That’s why, as Galbraith writes, “ virtuosity in persuasion” has to keep up with production. We need to be endlessly convinced the byproduct of endless production is important.

Whether we need or even wish the goods that are produced, their assured production means assured income for those who produce them. This serves the goal of economic security. Nothing else serves it so well. To falter on production, even though that production serves the most unimportant of requirements, is to expose some individuals somewhere to loss of employment and income. This cannot be allowed.

An affluent society becomes obsessed with a made up economy made up not of meaning, but mindless manufacturing. To question the obsession is to stop the machine all at once.

National Spirit

We view the production of some of the most frivolous goods with pride. We regard the production of some of the most significant and civilizing services with regret.

-John Galbraith

Galbraith claims our focus on production is misguided. Our never-ending focus on growth in the economy comes at the cost of public services. He makes the case that the biggest advancements in the United States have been linked to national programs when the government blocks all competition and takes all available resources for a single effort. Communism, nationalism. Pick your label.

He points to World War II, when antitrust laws and efficiency laws were suspended and there was an “astonishing” expansion in output. To him, this is proof that our concern for production is selective. If we really cared about “production” as the health and security and prosperity of the country, we would match public policy to production priorities. Instead, the affluent society lives between two worlds:

In the general view it is privately produced production that is important… public services, by comparison are an incubus…

At best public services are a necessary evil; at worst they are a malign tendency against which an alert community must exercise eternal vigilance.

Automobiles have an importance greater than the roads on which they are driven.”

To be okay with all of this, you have to avoid making any judgement on the goods that are being produced. The affluent society isn’t worried whether more cars or phones are more important than more food and shelter. Our made up economy is made to respect the producer and the production. The product is irrelevant. Our made up economy isn’t worried about whether anything is necessary or unnecessary, important or unimportant. Our made up economy is just worried about whether it’s being made and if we are making enough of it and making it fast enough.

After finishing The Affluent Society and drowning in headlines about AI, budget deficits, and job losses, I couldn’t help but think that if the economy is so clearly made up, aren’t all our jobs, too? Didn’t we just make everything up in order to give ourselves jobs in the first place? If production is the foundation for all fortunes and the foundation itself is flawed, where does that leave us?

Galbraith’s hope (in 1958) is that the affluent society decides to change priorities and start advertising and mobilizing for public services again. Not private products. He claims that production, hustle, this panic of “work,”, only fills a void that it has itself created. But there’s something deeper in the waters of this current era. It’s that we actually, truly, don’t know what’s important anymore. We are sitting in the bathwater of an overcooked culture that justifies any action with production.

The major takeaways of The Affluent Society are covered in Thoreau’s Walden (1854). As Thoreau warned us about conventional wisdom, too, explaining that:

Age is no better, hardly so well qualified an instructor as youth, for it has not profited so much as it has lost.

However, reminder that production isn’t everything has never felt so important, especially, as so many people fall prey to the production panic at the cost of their personality or personhood. As Thoreau would tell us, none of the “brute known as Creation” requires more than food and shelter. If you have that, you’ve pretty much made it.

Our true struggle in an affluent society is that when we have what we need, we start believing that we need what we want. In a haplessly, and helplessly connected made-up culture running on a made-up economy, we should always gut-check the urgency, the necessity, and the importance of the culture itself.

“If the individual’s wants are to be urgent they must be original with himself,” Galbraith writes. “They cannot be urgent if they must be contrived for him.”

That’s the difference between production and creation. The former is contrived for the consumer and the latter is original to the soul.

Want to learn more about hustle culture? Read “The Dark Side of Hustle Culture.”

Well considered article. Shared.

Important take on the social and psychic effects of disinvesting in a national vision based on public service and good. This piece, as much as I've ever read, gets at why the economy feels like a cynical, soulless shell-game played at the expense of our collective well-being.

I don't know where we begin rebuilding a noncommercial commons, and get people exchanging ideas in search of self. So many digital intermediaries between us all. So few mechanisms for fostering self-direction, and so many for reinforcing vanity and anxiety and phobia to extract our money. But it feels like an important project.

All of which to say: let me know if you want to make time for a little writerly confabulating this week ✍️🍻