Artwork: Drew Cookson

When I graduated from college and moved to Boston for my first job in 2010, I would count the number of people reading print books and compare them to the number of people reading Kindles.

Ebooks were taking over. Print books were dying. That’s what I thought. I made a whole website about it that still charges me a monthly fee.

I was in denial about the immensity of the problem: books are endangered.

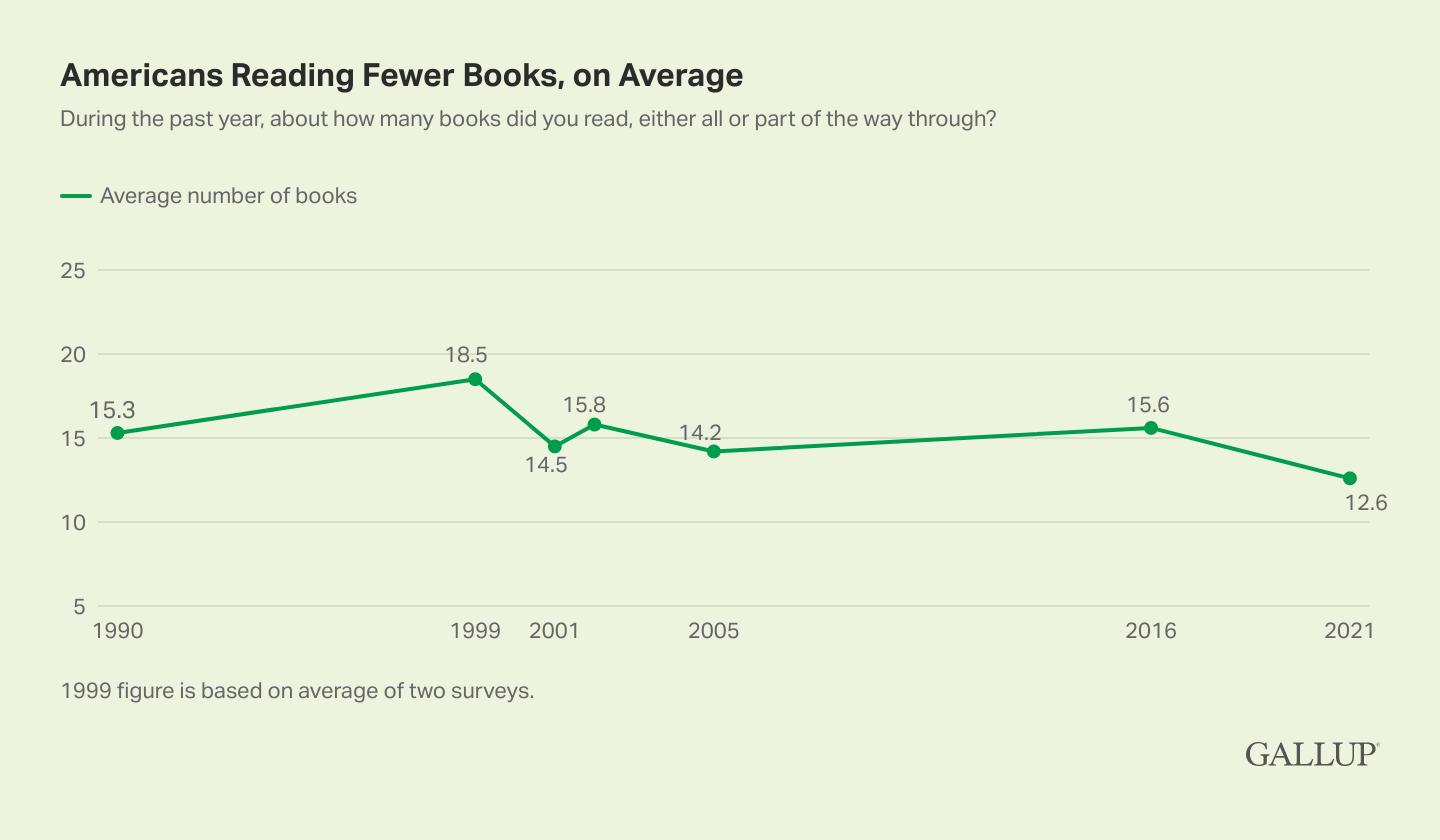

In 2021, Americans read an average of 12.6 books. That’s the least number of books ever recorded since the survey began, according to Gallup.

And it isn’t that the number of Americans didn’t read a single book last year. That number stayed stable. It’s the actual self-identified readers who are on the decline: Just 27% of Americans said they read 10 books or more. That’s eight percentage points less when compared to 2016.

College students, who should be forced to read at least three or four books by unreadable authors of the Romantic Period (sans Confessions of an English Opium Eater), are not doing their duty:

College graduates read an average of about six fewer books in 2021 than they did between 2002 and 2016, 14.6 versus 21.

Two weeks of isolation before stepping foot outside the campus? For two years?

Nope, still better things to do than read.

Women, our last literary hope, are also giving up reading:

Women read close to twice as many books as men did, but the gap has narrowed as the average U.S. woman read 15.7 books last year, compared with 19.3 between 2002 and 2016. Over the same period, men's readership declined by barely one book…

Attention is everything. The average American spends 5.4 hours on their phone and 5 hours watching TV every single day. That doesn’t leave much time to sit in one place and absorb heavy, beautiful novels.

The formula of the book’s death is simple:

Time spent reading generates the number of books read. The completion of a book is the consumption of the book as a product. This dictates the market for future books.

The funny part is that people read more than ever. They read texts. They read Instagram captions, Tik-Tok subtitles, and blog posts. It’s the book, and the concentration required that’s the problem.

This new project, Litverse, is about facing the inevitable evolution of literature without abandoning the things we’re leaving behind. Not everyone is going to read the classics, but if there’s a flash of perspective I can find and share that’s relevant to something today - the art is given a new life.

The goal of Litverse is to help refract the light of our screens through the lens of art.

Joan Didion, one of the finest American essayists in history, perceived the transformation ahead of us, and our future relationship with the written word from lifetimes away.

The Non Non Fungible Verse

Joan Didion sprung onto the literary scene with Slouching Toward Bethlehem (1968), a collection of essays with an ambivalent perspective on hippie culture set in San Francisco. The following collection, The White Album (1979), completes what I would identify as early Didion.

Each essay exhibits Didion’s trademark twists of compelling, curt conservativisms, faithfully manifested two generations later by MTV’s Daria.

The week of Didion’s passing was mostly marked by remembrances of interview exchanges like this:

If you could learn something new, what would it be?

How to work my television

Which word do you most overuse?

I don’t know

When are you most relaxed?

Listening to music.

What’s the best piece of advice you have for writers?

I don’t give writing advice.

What do you love best about New York City?

People ask me this a lot. The answer is, I don’t know, I just love it.

After reading Slouching Toward Bethlehem as an enjoyable indictment of the free love movement and “Goodbye to All That” as a triumphal indictment of New York (which Didion and I both left and crawled back to, thinking we both got it right each time, even if, as she put, “it is distinctly possible to stay at the fair too long”), my return to Didion essays was inevitable.

Thus, my embrace of The White Album.

The White Album features an essay where Didion sits in on a studio session with The Doors as they record what would become the album “Strange Days.” That’s what compelled me to finally buy it.

Jim Morrison, lead vocalist, is described as

“A 24 year-old graduate of UCLA who wore black vinyl pants with no underwear and tended to suggest some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact.”

Did she nail it or what?

Morrison arrives late, sits on the couch in the studio, lights a match, and lowers it toward his crotch.

The Doors, emblematic of The Summer of Love, are concluded in Didionesque truth: blunt, and beautiful, with the grammar of sentiment:

“I know that Jim Morrison died in Paris. I know that Linda Kasabian fled in search of the pastoral to New Hampshire, where I once visited her; she also visited me in New York, and we took our children on the State Island Ferry to see the Statue of Liberty. I also know that in 1975 Paul Ferguson, while serving a life sentence for the murder of Ramon Novarro, won first prize in a PEN fiction contest and announced plans to “Continue my writing.” Writing had helped him, he said, to “reflect on experience and see what it means.” Quite often, I reflect on the big house in Hollywood, on “Midnight Confessions, and on Roman Novarro and the fact that Roman Polanski and I are godparents to the same child, but writing has not yet helped me to see what it means.”

In the finest pieces, Didion reveals herself, and our humanity with an inspiring incredulity at the substance of life, a tone of terse shock that, when successful, electrifies the prose with sublime awe, elucidating the hidden corners of feelings with the sparks of a neo-Romanticism light, shimmering with the acceptance of the incomprehensible.

Didion loved the culture she dissected, because she was fascinated by it. I know that, because in the fantastic documentary of her life, she admits to being crazy about The Doors. The essay wasn’t critical or cynical. It was pure feeling.

Case closed.

The Promised Land

Didion witnessed the dawn of California’s Golden Age, that immortal illusion telegraphed in Don Draper’s summer suits or the patently unfortunate incidents of “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” Tarantino’s take on Hollywood’s reckoning in 1969.

California sunlight, Mad Man in foreground.

Her prose in these collections is sturdy and fearless, with a pioneering purpose. Maybe I’m overthinking it, but it kind of made sense when I found that Didion traces her roots to a great-great-great grandmother, Nancy Hardin Cornwall, who was a pioneer coming west with the Donner Party (luckily leaving them behind before the journey took a more cannibalistic direction).

Born in 1934, Didion saw California come alive. During her childhood in the thirties, the population of the Golden State was 5.6 million. When The White Album was published in 1979, the population had reached 23.6 million.

In a 1979 interview with The New York Times, Didion defined her perspective by her settler heritage:

The frontier legacy, she feels, has made her different, has ingrained in her a kind of hard-boiled individualism, an "ineptness at tolerating the complexities of postindustrial life.

In The White Album, Didion’s prose is chosen as professionally as gems, the passages polished just as lovingly as those found in Slouching Toward Bethlehem, but the subjects can fall flat and leave the prose feeling winded.

I can imagine the thrill of this collection in the early eighties, when California sunlight still must have seemed as fantastical as pixie dust to readers who lived in places with more than one season. The titular essay can still leave you breathless with the beauty and tragedy of the period. Other essays, unenchanted with the novelty of the era, can feel unrealized, as if holding back from a revelation never more than a few more paragraphs away.

That said, reading the collection in the age of a post-book society, one essay stood out: “Good Citizens.”

Visions of a Meta Meeting

In “Good Citizens,” Didion observes Nancy Reagan in front of a TV crew. Her goal is to write about the encounter, but her potential to ask questions is eliminated by the TV crew’s eagerness to produce. Didion starts to realize that the image of Nancy Reagan, the production of that perception, will displace any story she writes about the experience.

In front of the cameras, Reagan becomes a powerful puppet:

Nancy Reagan is a very attentive lister. The television crew wanted to watch her, the newsman said, while she was doing precisely what she would ordinarily be doing on a Tuesday morning at home. We seemed to be on the verge of exploring certain media frontiers: the television newsman and the two cameraman could watch Nancy Reagan being watched by me, or I could watch Nancy Reagan being watched by the three of them, or one of the cameramen could step back and do a cinéma vérité study of the rest of us watching and being watched by one another.

Would Nancy Reagon really be doing this on Tuesday? What is the power of suggestion? At what point does she become not Nancy Reagan, First Lady, but an actress influenced by what the crew believes the crowd wants to see?

Didion is examining who dictates the final production of perception in a marketplace of images. That wasn’t the purpose of her visit with Nancy Reagan. It was likely to understand her, or what she stood for. With the stifling presence of the camera, Didion wasn’t allowed to ask about any pressing issues. All that most Americans would see and remember from the day was this: Nancy Reagan smiling in a garden.

Source: Elle

Didion recognizes here that an ugly scramble of words with no pictures will reach fewer people, and the experience itself had become fake as soon as the TV crew told Nancy Reagon what to do.

A picture is worth a thousand words and a thousand shares. But all that awareness becomes meaningless when everyone is speaking a different language.

Life Without Context

Didion’s day in Nancy Reagan’s garden predicted the opaque tidal wave of images we see as soon as we look at a screen. Forget the camera crew. Now, everyone can produce themselves as a product. The beliefs we form are based on the language we speak, the shared vocabulary and, let’s be honest, memes as complex as hieroglyphs to people outside the temple. We furnish the purity of our position with idols and imagery, collected and dedicated to our crusade for consistency.

Didion foresaw that the written word, that slow and unwieldy thing proven to train our brains for empathy, would be discarded in favor for higher impact illusions. Sacrificing the calculated contusion of concentration that reading requires in favor of the infinity of immediate and instantaneous images in front of us, we’re aware of everything, but know nothing.

In all the discussion of the metaverse, it’s obvious we already live in one. And the metaverse is a place where it’s really, really hard to concentrate. The bad news, the good news, someone else’s news, someone else’s views, find us wherever we are. New meanings flow over us, giving us no time to do much but swim.

All because we can’t put down the phone and pick up a book.

But that’s only if I accept the non-negotiable definition of books as a printed product to be consumed from start to finish. I think that more people might read if they can see, well, little snippets of the kind of writing they’re missing. They just need a little clickbaiting of a few passages of it first.

People are reading. They’re seeking meaning. They’re just doing it differently. And that’s why Litverse is here: to help bring words of wisdom from the past, present, and future along for the ride. Every essay will at least have some great quotes from great artists, writers, and creators, even if the rest of the writing is bad.

So let’s enter the Litverse together.

Highly recommend "Play It As It Lays" if you like Didion - it's the most viciously unsentimental depiction of Southern California you can get. The foreword author described recommending the book to others in the same way you'd recommend they check out a nest of vipers, which is a tidy, apt metaphor.