(Part 1 of this Litverse series can be found here)

On a cold spring night on a Tuesday on the Brooklyn waterfront where the East River shrugged off the candlelight of the Manhattan skyline, I entered the superchurch chic of powerHouse Books. I had come to the bookstore (now relocated to a neighborhood with cheaper rent) to hear from one of our greatest living novelists, Salman Rushdie, who had just published a book about people losing their gravity and floating around, or something.

Rushdie’s natural magnetism and practiced charisma sparked the factory floor ceilings. This is a man who has been famous for decades but, simultaneously, had a bounty on his head and keeps publishing books. A man who published a new book after being stabbed by a would-be assassin.

“Where do you get inspiration from?” an audience member asked.

His eyes twinkled behind his glasses. Rushdie smiled smug and sympathetic. “I love this question,” he told the audience. “The answer is a big book. I have a big book where I flip through the pages and just grab an idea any time.”

The crowd laughed.

A tactful question about the bounty on his head: “Are you ever afraid to express something, given your experiences?”

“Never,” Rushdie said firmly. “You can never be afraid to express something in your writing. Otherwise, you turn into Dan Brown.”

I didn’t buy the book, it sounded kind of dumb. But I left the reading with a new question about creativity as a product. What is the force that makes us create? Where does it come from? Does it control us or do we control it? Can we tell the difference?

Last week, we covered how some art must be “unconscious” - contrary to the traditional portrait of an artist is a pen-chewing, hair-plucking, teeth-grinding, neurotic tortured by how the work will be received by the audience. Some artists summon and channel creativity instead of prying, coaxing it out of crevices and bone-hard caverns with “process” and “discipline” and “intention.”

The Ancient Greeks thought that unconscious art was the only way to create art. According to Plato, creativity is a possession, not a process.

Aesthetic Insanity

Plato’s philosophy of aesthetic explains the poet as “wholly an instrument of the divine.” The poetry is produced from something “purely instinctive and unconscious.”

In 1932’s Art and Artist, psychologist Otto Rank cites the theory that:

Plato not only neglects the role of consciousness, but completely eliminates it, putting in its place mania, a being outside oneself, a divine inspiration… The first give of divine madness is unctuous prophecy… Plato says that the poet, when he seats himself on the tripod of the Muses, ‘is not in his sense, but, like a fountain, lets flow what comes to him, and often contradicts himself without knowing whether the one or the other thing he says is the truth.

Rank concludes that Ancient Greece’s culture recognized art as something not created within us but something sent through us by a higher power. This makes sense, given that people believed in twelve gods at the time. That meant plenty of different sources for poetry possessions.

And how do you receive this divine power? The elimination of reason, Plato wrote. In simple terms: Going crazy is a necessary way to allow the art through you. Art is received, not created, and inspiration is the dance partner of psychosis, not creative “process.” Art is creation first, culture second. Possesion, always.

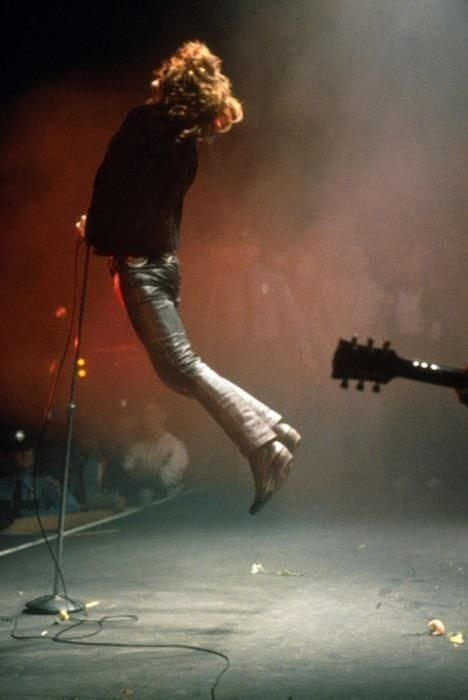

Inspiration through insanity. This is the way to see Doors frontman Jim Morrison’s creative psychosis: the art is produced through possession.

“Possession” is literal in Morrison’s case. There is a single event in his childhood that became his destiny. As Sugerman and Hopkins write, Morrison was in the car with his family outside Albuquerque on the highway from Santa Fe and the family stopped beside an overturned truck where Pueblo Indians were dying on the road (the book is authoritatively specific about the Pueblo part). Morrison describes seeing this random car crash as “the most important moment of my life.” From that moment forward, for the rest of his life, Morrison decided he was inhabited and guided by Native American spirits. This is materially different from the naked hippies interested in native culture. Morrison really believed this without question. The incident haunts a number of songs. As he writes in the post-humous, spoken word Ghost Song:

Indians scattered

On dawn's highway bleeding

Ghosts crowd the young child's

Fragile eggshell mind

His repression of the event is an expression. Any contemporary artist claiming to be a host for Native American spirits would be the subject of ridicule and cancelations. For Morrison, his unwavering belief in this merger is the source of the unique spirituality in his art. His performances at concerts were ritualistic. He called the performances a “ceremony.” He channeled for the art, not the audience. It was the spirits that made him do it, and he wasn’t the only one who thought that.

As keyboardist Ray Manzarek explained:

Jim was not a showman. He was a shaman… He was possessed by a rage to live. That was his trip, his gift.

Let’s linger on Manzarek’s claim here: Morrison was possessed by “a rage to live.” This is a counter-intuitive image of a traditional 27 Club member, like the morose Cobain or the skeletal Winehouse, both determined to escape the tragedies of their weaknesses into the shadows they confused for their selves.

Morrison, dead from an overdose at 27, must have seen substances as a way to summon the spirits and live life more powerfully, more truthfully. At least if we’re to believe Manzarek, whose post-humous interpretation sounds a little optimistic. Still, there’s no denying Morrison’s vigorous defense of alcohol. As the book quotes him:

I enjoy drinking… it’s like gambling: you go out for a night of drinking, and you don’t know where you’ll ed up the next moaning. It could be good, could be a disaster, it’s a throw of the dice. The difference between suicide and slow capitulation.

Morrison’s mission was always more clear than his methods: break on through to the other side. The art is the madness, not the method. The Doors, one of the best-selling bands of all-time with almost as many albums sold as Taylor Swift despite only touring for five years, wanted to be the medium for listeners to cleanse the doors of perception, taking their name from William Blake’s poem “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell” (1790-1793). Specifically the line:

If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.

From the very start, the purpose of the music was to help people break on through to the other side. Whatever was on that other side. As Morrison put it in 1968:

I think there are a lot of images and feelings in us that can hardly move freely in our everyday life. However, when they do come out, they often manifest in perverse forms. It’s the dark side of things. The more civilized we become on the surface, the stronger is the other side’s demands. Think of it (the Doors) as a séance in an environment that has become life-threatening: cold, limiting. People feel dead in this bad countryside. We collect them for such a séance to recall, reconcile and expel the spirit of the dead. With chanting, dancing, singing and music, we are trying to heal the disease, trying to bring harmony back into the world.

This spiritual sensitivity shows a shameless and naked approach to art. So does the book’s claim that Morrison took acid more than 250 times. When it came to channeling this art, breaking through to the other side, over and over, finding the divine inspiration that would possess him like poets of antiquity, Morrison accessed his addictions unapologetically. He became a shaman through self-sacrifice, self-destruction. How else could he carry the message back from the other side?

The trouble started when he realized he had become a product, not a poet. Is there a difference? Was there ever? Let’s find out in Part 3 next week. Read Part 1 here and Part 3 here.

Alcohol and acid might cleanse a door or two, and allow for a few ghosts/Dionysian spirits to come knocking at our psychic margins. But I also think art needs to function on a sober level, too, wherein the artist makes conscious choices about communicating experience. I love The Doors, but a big portion of their catalogue always strikes me as pretentious onanism.

Channel the flow and ride it out, by all means - but have an editor you trust to pull you out of the stream, too. Because self-awareness and perspective are critical tools in the artist's toolkit, no matter the medium, and we all need some help developing them.

Jim Morrison was a fragile marble icon, he thrived on poetry, yet withered with music, he wasn’t egocentric or high and mighty, he only wanted to be left alone to create his magical potions of verse and gilded passages of time’s precious keepsakes. Jim was a poet first, a musician second, and third, a divine drunk. I loved The Doors and Morrison, so, why discard Jim as some dime relic?