If you need any proof that one person contains “multitudes” (as Whitman says), you only need to do one simple thing: go on vacation. In a pinch, leave work a few hours early and simply wander. No GPS.

A vacation is a break from the daily grind. That’s what we call it when we don’t follow our routine. If routine dictates our lifestyle and lifestyle defines our individual self, a vacation is a break from our tired daily self.

Research proves the point. One survey found that 65% of couples know it’s time to go on a vacation when they feel “disconnected” from their partner. Given that most humans have no electrical outlet, this word is always understood as a disconnect from the self and an urge to explore our other multitudes.

Or, if you want to be cynical about it, like 1950s sociologist Charles Wright Mills, we pay money to go on vacation in order to pretend to be the self we wish we were.

This is the nefarious defintion of “vacations” in his classic work, White Collar: The American Middle Classes. And I can’t disagree more. Escapism is good. But why do we have so many multitudes anyway?

Vacationing in the Personality Market

Born in Texas in 1916, sociologist Charles Wright Mills lived only to the age of forty-five, passing away in 1962 from a fourth and final heart attack. He worked hard and fast - a trait to which his wife and three ex-wives could likely attest.

I’ve read two of his books: The Power Elite (1956) and White Collar (1952).

In The Power Elite, Mills attributes the death of agrarian and craft industries and local economies to the unstoppable determination of the one percent to consume free enterprise and leave behind “two or three hundred corporations.”

In White Collar, Mills turns his ferocious focus one rung down to eviscerate the “managerial class” that helps run the machine. The book shares many grim assessments of white collar life and Mills establishes a narrative that is counter-intuitive to the mythical postwar boom of America that he witnessed in the fifties. As described by The American Machinist:

By 1955, the U.S., with only 6% of the world's population, was turning out half the world's goods. But manufacturing saw the beginning of a disturbing trend. In 1956, for the first time, white-collar workers outnumbered blue-collar employees. Between 1947 and 1957, the number of factory operatives declined 4% while clerical workers increased 23% and the salaried middle class 61%.

Mills dismisses productivity and rising living standards at the outset of White Collar and highlights the danger of labor that depends on a “personality market” that trades on the currency of conformity. Mills is concerned that corporate values subsume the multitudes and leave only a single, automatic self behind, writing:

In all work involving the personality market… one’s personality and personal traits become part of the means of production. In this sense a person instrumentalizes and externalizes intimate features of his person and disposition. In certain white collar areas, the rise of personality markets has carried self and social alienation to explicit extremes.

Fears of self-alienation may seem antiquated in a modern economy where self-expression is treated as a constitutional right, but what Mills also dissects is the disassociation between white collar workers and the self that produces the labor, which Apple+’s “Severance” made so tangible.

This ‘severance’ from employees and their work is a real thing, according to Gallup:

After wild fluctuations in 2020, and hitting a peak level early this year, employee engagement has settled down in the U.S.

Currently, 36% of U.S. employees are engaged in their work and workplace -- which matches Gallup's composite percentage of engaged employees in 2020. Globally, 20% of employees are engaged at work.

Unengaged at work but forced to weaponize our personality to become the labor, Mills believes the primary self of a white collar worker streamlines all our multitudes to become only the work, with a shadow self quivering behind it.

Multitudes in Stasis

Routine keeps us within the box of a single self. Vacations allow us to access our multitudes. But is every vacation based on a lie?

Here’s what Mills says about taking a break:

On vacation, one can buy the feeling, even if only for a short time, of higher status. The expensive resort, where one is not known, the swank hotel, even if for three days and nights, the cruise first class - for a week. Much vacation apparatus is geared to these status cycles; the staffs as well as clientele plays-act the whole set-up as if mutually consenting to be part of the successful illusion. For such experiences once a year, sacrifices are often made in long stretches of gray weekdays. The bright two weeks feed the dream life of the dull pull.

Traveling can feel like a dream life. So can big events that put your mind elsewhere, whether concert, wedding, or NASCAR race.

One could claim, as Mills does, that the orchestrated obsequiousness of hospitality staff or the interplanar euphoria of a crowd is nothing more than a play in which both attendee and staff are the actors creating a drama in which other selves are performed.

There’s no proof that this argument is necessarily wrong.

But Mills, in my opinion, overpowers his thesis with his grumpiness and overlooks a very basic fact: a vacation self shouldn’t last forever.

Escapism is a moral good, and so is routine.

The Necessity of the Code Switch

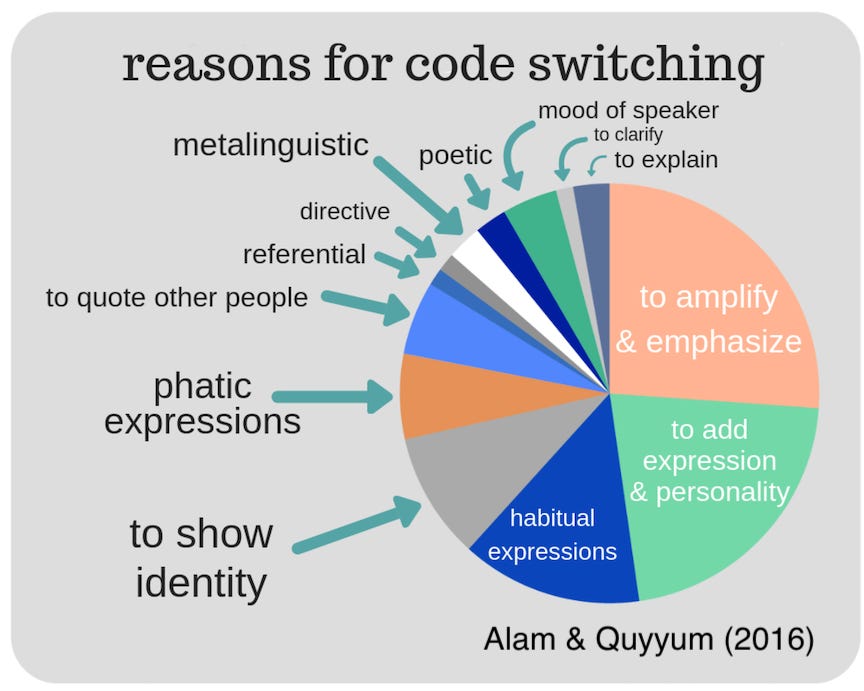

No matter how many selves we may have, it’s impossible to rest after too much abstraction of a personality or a vacation that lasts too long. We can’t live in our multitudes forever, because humans crave stability. Whether white collar work or family obligations, that stable self isn’t necessarily alienated from the rest of our self. Every job, every day-to-day function requires what some would call “code-switching” and others may call “a personality.”

White collar workers aren’t static even when performing a routine. Yet, beneath it all, we often wonder what else is out there. We fantasize about “taking the plunge” or “going off the rails.”

Or, as Ernest Becker’s 1974 book The Denial of Death (which won the Pulitzer Prize two months after he himself died and I found on the sidewalk in SoHo broken in half and on sale for a dollar in 2022) puts it, every man is beaten by the day-to-day because:

[Every man] fails to face up to the existential truth of his situation - the truth that he is an inner symbolic self, which signifies a certain freedom, and that he is bound by a finite body, which limits that freedom.

The multitudes are menacing. It can be healthy to hold them in stasis.

We hide behind a single self, because the infinite is a void.

Becker is less sympathetic to a routine self, which, in citing Søren Kierkegaard, he calls “a trivial life” that helps man avoid the full horizon of experience. Kierkegaard, a 19th century Dutch philosopher and son of a maid who cleaned the house of his father, confirms that the types of people who never take a break from that singular self, should be seen as an “automatic cultural man” who only recognizes his self through external actors. A pure product of the personality market.

Never married and burned by his long-time love in a failed engagement, Kierkegaard’s work exudes the eternal loneliness of a spiteful self seeking who fears the shallowness of necessary living. In Kierkegaard’s case, the life of a bachelor.

The Denial of Death posits that every human lives between two extremes: the necessary and the possible. Sticking out our head too far into the infinite of the possible guarantees that we might lose it. Following the line too closely of the necessary and our reflexes become automatic and, so too, does our self.

Like Calvin when he’s Spaceman Spiff, our lives are juxtaposed with all sorts of other selves. This is freedom. But, like Spaceman Spiff, we all have to crash land back to our inescapable home planet.

Mills believes that vacations are only vain vaudevilles in search of validation. But escapism isn’t about looking for answers somewhere else - it’s simply about escaping to another self for a while. People often talk about “finding themselves” when they travel, but what they really want to do is explore different selves, take a few bits and pieces, and come back to that normal, necessary life afterwards.

If vacations are so wrong, according to Mills, you might be wondering how he describes work. Sorry, that’s no good, either. Mills believes hard work itself is the byproduct of what he calls “the status panic.” Going on vacation is just a cheat code to this cycle in creating a “holiday image” of the self:

Psychologically, status cycles provide, for brief periods of time, a holiday image of self, which contrasts sharply with the self-image of everyday reality. They provide a temporary satisfaction of the person’s prized image of self, thus permitting him to cling to a false consciousness of his status position.”

I can just imagine his honeymoon with his fourth wife, maybe somewhere exotic on the beach. Mills is getting a sunburn and drinking coconut rum and writing:

The machinery of amusement and the status cycle sustain the illusionary world in which many white-collar people now live.

Economy of Creation

I’ve been haunted by White Collar for years. If you read it too closely, it can threaten to steal your joy from you. The personality market, the vacation dependent on the holiday image of the self, and a status panic among white collar jobs are still relevant concepts to anyone who’s already insecure in their selfhood, or spends too much time on LinkedIn or Instagram. These feelings of fragmentation fuel the furnace in which the fires of social media fry our perceptions daily. But the incendiary implications of this institutional injustice that Mills always takes for granted no longer exist for white collar workers.

Mindless documentation, strict office hierarchy and corporate rituals and even commuting have been made obsolete by a few founders showing up in shorts. Authenticity and originality and creativity are values now because, in a sense, even work is escapism. Especially if your office or your brand or your product is cool enough.

Overall, 90% of tech workers say they’re at least somewhat satisfied with their jobs.

To be honest, the research here shows that pretty much everyone seems kind of happy. Maybe a lack of file cabinets helps?

The threat today isn’t conformity. It’s conflation.

Research shows that Instagram use directly causes body image issues, eating disorders, and feelings of inferiority. Just grab your phone to browse Twitter or Instagram and scroll for a few minutes.

Do you feel better or worse? What self was that, consuming that information?

Where did all our multitudes go?

The Great Smushing

In Wired, writer Zak Jason identifies the streamlining of our identities as “The Great Smushing.”

The proportion of our lives that we compressed into our smartphones jumped at about the same rate. The average American adult now spends more than nine hours a day planted in front of a screen, more than half of our waking lives smushed into an Apple, Google, or Microsoft device.

We might like our jobs, and that constant and automatic self, a little too much: employee burnout affects three-quarters of workers.

As Jason notes:

Each of us has 86 billion neurons, and forms some 6,000 thoughts a day. The idea that we must rein all of that into a single identity is fantastical. But the smushing makes that fantasy a suffocating reality.

The solution is clear: we all have to go on vacation and turn off our phones. We have 24/7 access to our multitudes, to all that’s possible, but we’ve tied them all together like so many balloons. But there’s no necessary self holding the strings. By dispersing so much of ourselves through technology, we’ve found it hard to keep track of not the possible self, which we have in infinite supply, but that necessary self we fear is too boring, too predictable, too linear.

White Collar presents this radical atomization of personality in the 1950s:

Organized irresponsibility, in this impersonal sense, is a leading characteristic of industrial societies everywhere.

On the personality markets, emotions become ceremonial gestures by which status is claimed, alienated from the inner feelings they supposedly express. Self-estrangement is thus inherent in the fetishism of appearance.”

We now have the technology to go on vacation in our pocket.

Is it work? Is it leisure? Is it the possible or the necessary?

We’re not sure anymore, just like Mills foretold:

Just as work is made empty by the process of alienation, so leisure is made hollow by status snobbery and the demands of emulative consumption… The machinery of amusement and the status cycle sustain the illusionary world in which many white-collar people now live.

In the last weeks of summer, maybe it’s time to consider less pumping of our numbers in the personality market and more putting our phones in another room for a few hours or turning off the TV and paying attention to life itself.

The present self, that self we spend so much time with, especially when we’re not distracted, is a gift. A vacation from the personality market is free. No plane tickets required.

Great Prose Alert ⚠️: "Incendiary implications of this institutional injustice" *doffs Alliteration Cap respectfully*

Was reminded of what a great wedding guest you were during the vacation-selves sections, and how in large part that was due to how you live out your own advice when away from work. Always love it when those I admire reject hypocrisy 😆 Thanks again for always being present, not chasing clout on socials, and for always being there with a glass of Redbreast 🥃