At around 200 pages into Termination Shock by Neal Stephenson, I sat back with a question on my mind: what is a book?

Is it a unit of art with a beginning and end that we value by virtue of variables like prose, characters, and plot? And, if that’s true, is it okay that Stephenson insists on mixing that single unit of book with seventy-five percent exposition, diluting the interesting oil of an idea with a motionless ocean of pages lacking even the gentle swell of quotation marks?

This is a common challenge of “hard” sci-fi like Termination Shock, which can often read more like a string of loosely connected Wikipedia entries than a “techno-thriller.”

But at least I came away with a better understanding of hogs.

Exposition: Impossible

As Wikipedia tells us:

Hard science fiction is a category of science fiction characterized by concern for scientific accuracy and logic.

As Wikipedia does not tell us, “hard sci-fi” can betray readers with too much “concern for scientific accuracy and logic.” At its worst, hard sci fi gets lost in the religion of itself, serving sermons of cold facts to assure readers true salvation lies not in the joy of reading, but the joy of learning how something works.

In Termination Shock, Stephenson achieves this requirement through eccentric Texas billionaire TR Stereotype. Sorry, TR Schmidt. This is a name brought to us by the same author of Snow Crash (1992), the cyberpunk masterpiece in which the main character named Hiro Protagonist.

But things have changed since Snow Crash.

In 1992, Microsoft released Windows 3.1. Sir Mix-A-Lot’s immortal ode to backsides, “Baby Got Back,” was the #2 song in the country. Nirvana had just released “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” which sat thirty places lower than “Baby Got Back” on the charts. The Soviet Union had fallen just one year ago.

Masses of disaffected teenagers, unmoored by nationalism and living a life when the draft never reminded them of the thoughtless brevity of life, found sanctuary in cynicism gilded with techno-optimism. The illusion of tech sexiness culminated in The Matrix (1999) but the legacy of late nineties cyberpunk was more accurately depicted by Grandma’s Boy (2006) with scenes featuring the trench-coat wearing boss like this:

In 2021’s Termination Shock, we find a Stephenson who, like our current culture today, has lost all sense of irony in favor of a relentless focus on existential danger. Even the technology featured in the book is less sleek and sexy than it is clunky and awkward. The cool mysterious metaverse readers encountered in Snow Crash or the bizarre Victorian nanotechnology in The Diamond Age are forsaken here for a Texan wasteland plied with old railroads, piled with sulfur, and poked with abandoned mines. People are miserable, and it is hot.

TR Schmidt has assembled a cabal of ministers and royalty in the wasteland to showcase his great project: a solution to save the world from climate change.

Traveling on a train through this hellscape to the site for his sales demo, TR Schmidt violently educates the cabal and the reader through a series of exchanges such as:

“This is only part of the demo we’ll be showing to the media… We are working on a bigger presentation. But I thought you might get a kick out of it.”

“Could you first say more about the media?” Saska inquired. “I was told-”

“All NDAed, all embargoed. As many people discussed with your people when we set this up,” T.R assured her. “Sooner or later, according your man Willem, you’re going to make it public that you visited the site.”

“We have to,” Saskia said.

“The agreement was, you can do that on your own timetable. That agreement stands, Your Majesty. And it’s up to you whether you take a pro, anti-, or neutral position.”

If you lost track of it, it’s because it doesn’t mean anything. Writers often eliminate operational language. Not Stephenson. Every word is tracked diligently. This isn’t Stephenson’s fault. He’s a hyper-realist, a multi-faceted genius. His prediction with his prose is that every reader feels the same thrill from learning the details as he does. The difference since the nineties is that Stephenson’s later work sometimes loses the edgy coolness that once balanced novels like Snow Crash and The Diamond Age so well.

The passage above takes place on page 224 and ends on page 227. Our interchangeable cast is at dinner on a train car rattling through a near-future Texas with heat so extreme that people need to wear suits to go outside during the day. The scene begins with a text conversation between the smart, sassy, airplane-flying Queen of the Netherlands, Frederika Mathilde Louisa Saskia who, with the potential annihilation of her country at stake due to rising sea levels and an important dinner to attend with other dignitaries, is occupied by how she can get laid.

Preparing for the dinner with the man who may hold the technology to save the world, Saskia texts her daughter, a teenager, about potential people she could have sex with, all of whom are on the train:

>Possible third target identified.

>Who is he?

>She

Her daughter, the Princess of the Netherlands, asks for a picture.

>My darling, there is absolutely no way that you are getting a picture.

>Aww!

>I hope you sleep well. Going into a fancy dinner.

>I hope you don’t sleep AT ALL

This befuddled relationship, with a whisper of whimsy, a trace of irony as faint as smoke, kicks off to a dinner conversation that lasts for ten beefy pages of TR Schmidt demo talk.

No matter what’s being said and which character is saying it, you can count on it being derailed into Wikipedia territory sooner or later, with facts unloaded at random, as when Saskia doesn’t immediately provide a reaction to Schmidt’s boring speech when he asks for her opinion.

“Why, you shall have to ask me tomorrow,” Saskia answered. “Like a good Texas poker player, you don’t show your hand too soon.

“You’re too kind, Your Majesty. I was just asking in a more general sense about where it’s all going.”

“Perhaps you should have invited a philosopher! I can only represent the perspective of the Netherlands, of course.

“The Netherlands,” Bob said, through a mouthful of bison, then swallowed. His face betokening the right amount of dry amusement. “A place whose very name means low country.”

“I am aware of its meaning and of its altitude, Robert,” Saskia returned, with a glance at Daia, who was enjoying the little jab at her husband.

“But it really is the eight-hundred-pound gorilla in all this, isn’t it?” Bob asked.

“The City of London is not without a stake in the matter.”

“The Romans, at least, had the good sense to build on a hill,” Bob returned. “Oh, some of the property down along the river will be flooded. But it’s been decades since we began moving the server rooms, the generators, all that up out of the cellars to the roofs. Slow and steady, but with very material progress. We could absorb a 1953 event rather easily. Not that we wouldn’t get our hair mussed, but…”

The characters fail here, because the dialogue focuses on facts, not feelings, and these facts are forced indiscriminately into the mouths of dignitaries whose names don’t even matter.

This is hard sci-fi, after all. Read any page of Termination Shock and you will learn something. Stephenson could almost certainly build an extremely interesting digital literature project with personalized content made for the metaverse.

Want even harder sci-fi? You can choose to get extra exposition and more facts and hyperlinks to videos and Wikipedia entries.

More of a Jack Vance fan? GPT-3 could inject more imagery, spend more time on interactions between characters and action. Maybe you could input your favorite movies and books to help it personalize.

Termination Shock cannot be said to be bad. It’s simply a “book” disengaged from itself, the prose a machine determined to bang parts together, searching for a connection between facts and feelings that doesn’t exist.

Going Out with a CLANG

When Neal Stephenson launched a Kickstarter for a video game that promised backers immersive sword combat with motion control in 2012, a project named CLANG that surpassed the $500,000 goal and failed to produce anything for it, an injustice that so enraged backers that a class action lawsuit was formed, Stephenson showed a humble and painful self-awareness about his hubris:

"I probably focused too much on historical accuracy and not enough on making it sufficiently fun to attract additional investment."

For the record, CLANG looked kind of intriguing, whatever it was supposed to be.

If I were Stephenson, I would try to sell CLANG to Switch. I could see people swinging at each other in their living rooms.

CLANG suffered from the same mortal wound as his later work. Stephenson asks for investment, but gets carried away. In the case of CLANG, the investment was financial. For the readers of Termination Shock, the investment Stephenson asks emotional investment.

Stephenson’s work evokes emotion from a readership that experiences emotion from explanation. That’s why his readership includes founders like Bill Gates, Peter Thiel, and Sergey Brin. This is a man who worked at the spaceship company owned by Jeff Bezos. He’s the visionary who allegedly inspired the inventors of Google Earth. He defined and popularized the terms “avatar” and “metaverse.”

It’s impossible and unserious to disrespect Stephenson’s work, which is always striving to be hopeful, bold, ambitious, and curious. His mind is tireless and curious, but, increasingly, tiresomely curious. His power to grasp and understand and express is now an enemy of itself.

Termination Shock is too long.

The Dissolution Decade

Snow Crash, published in 1992, is 350 pages. Termination Shock, published in 2020, is 720 pages. If this was a corporate environment, Stephenson’s work could be said to be guilty of “scope creep.”

The other part is simpler: Stephenson is in need of an editor.

A few additional drafts of Termination Shock could have turned what is a promising work into something closer to a vision that truly does describe so delicately an urgency about our interconnected future, becoming more influential by being more actionable and more accessible.

Or as Hemingway, not exactly known for exposition in his own work, once said:

“The first draft of anything is shit.”

Temperature Thriller

During the third sales demo from TR Schmidt, in which our fearless Queen descends into a mine hundreds of feet below the surface to listen to the thrilling hardware specifications, chemistry interactions, and environmental effects of a sulfur cannon, I finally surrendered and gave up on the book. I assume this climate-saving weapon has consequences. But without the visceral impact of the problem, Termination Shock becomes the same academic papers that warn us on a monthly basis of our doom.

Since the 2000s, we’ve abstracted technology from religious optimism to slick sexy transcendence and now examine it with moral philosophy. This explains the bizarre change in sci-fi- book covers since the millennium, as almost all these books are forced to pretend to proffer some new life lesson, rather than character-driven plot.

The thesis of Termination Shock is whether there can be a cure-all for climate change without consequences. The answer is uninteresting because it is obvious, unsolvable, and subjective all at the same time. Ambiguous morality is not a good villain. Termination Shock is museum-grade science fiction, a piece to be put in a college library or cited in a dissertation.

There is, however, a real-life threat described in chilling detail in the book: feral hogs. And, even though I gave up on Termination Shock, I now know more about the “feral swine bomb” than I could have ever expected.

Why is Neal Stephenson so obsessed with hogs?

I decided to find out.

The Feral Swine Bomb

In Termination Shock, we’re introduced to what appears to be a heartwarming story of a girl and her wild hog. In a brutal turn of events, the hog eats the girl and goes on a rampage, only to be killed at an airport by the girl’s father in what is one of the strangest tales of vengeance ever written.

The danger isn’t an exaggeration.

Consider this gruesome scene reported from Anahuac, Texas this year:

Christine Rollins, 59, was a caretaker of an elderly couple who live in the home. The body was discovered in the yard between where she parked the car and the front door of the home. The official cause of death was listed as “exsanguination due to feral hog assault.” Deputies noted she had many injuries and the seen was very gruesome.

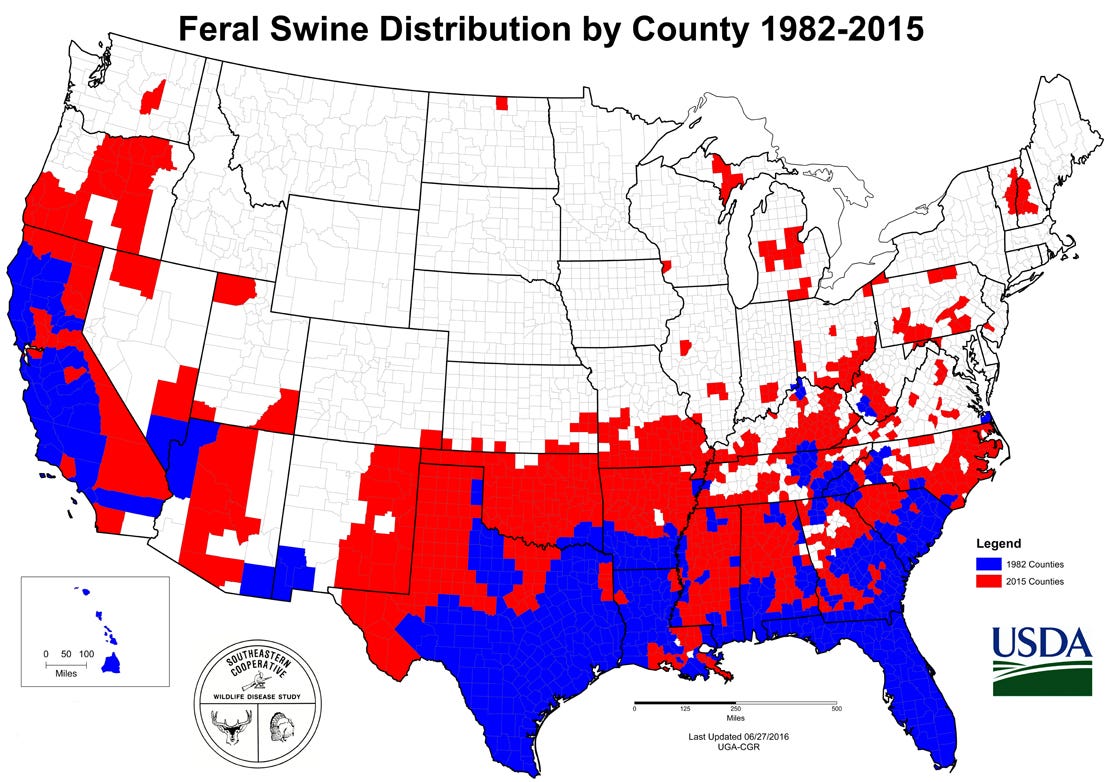

The first thing to know about feral hogs is that they’re big. Upwards of 400 pounds. The second thing is that they’re everywhere: there are six million of them in the US across thirty-five states and counting. In one year, a female can have three litters. Litters can be up to twelve piglets.

Feral swine do $2.5 billion damage a year. These demonic boars are also ticking biological time bombs, carrying 30 different viruses and bacteria in addition to hosting some forty parasites. Most are transmittable to humans and pets.

Remember Swine Flu? It’s from pigs. It’s killed hundreds of thousands of people. The population chart below should be read like the map of a spreading plague.

Did I mention they’re almost impossible to kill?

As a hunter notes in The Montrose Daily Press:

I know personally of a large ranch in Texas that attempted to use an aerial assault program to eradicate the interlopers. A team flew a helicopter over their 60-thousand-acre ranch and shot the hogs from the air. The crew flew hundreds of sorties over a six-month period and permanently eliminated close to five thousand hogs.

For almost a year, the ranch owners were busy backslapping each other in congratulations over having conquered their hog problem. Not so fast fellas: within another year the hogs were back in droves. Two years after the assault, the numbers were right back where they started. The ranch manager told me that a tactical nuke would not get rid of these hogs, and I believe him.

Dawn of the Super Pig

Forget dogs, pigs are thought to be smarter than chimps. They feel stress, pain, fear, and joy. They’re extremely social and form hierarchies, with more than twenty sounds to communicate with each other. They’ve even been documented as decorating their living space with flowers. Also, they’re extremely clean when not living in cages.

Transfer that social intelligence into a 400+ pound animal that can run more than 30 miles an hour, armed with razor-sharp tusks. Forget Spider Pig. These super pigs are super soldiers and they’re an invasive, highly intelligent, highly adaptable adversary.

Out west, my friend encountered a family of feral swine while camping deep in the woods at night. He said the birds stopped singing. Everything went quiet. When he turned the flashlight on, he saw a family of wild pigs staring back. He kept his eyes on the tusks and he screamed three times. The pigs retreated to a hill, without showing fear.

“They could have taken me,” he told me solemnly. “They were thinking about it.”

Feral swine today are a mutant breed of pigs and wild boars. They’re a real and immediate threat. I felt an exotic excitement when Termination Shock opened and it seemed that Stephenson would somehow make the pigs the enemy. Yet once the hog hunter avenges his daughter, my favorite part of the book vanished.

Compared to climate change, the swine conflict is much more romantic. It’s a revenge tale for murder on an industrial scale. Imagine if these feral swine can hear the millions of screams from pigs in the cages, preserved in a state of mindless torture to satisfy the demand for hamburgers and bacon.

Imagine if they blame us.

Just like climate change, the feral swine time bomb is the reckoning of humanity’s gluttony. It’s just more simple and more tangible. Like Termination Shock suggests, no mass production comes without sacrifice. We live complicit in this consequence, unconscious of it. We’re living life through the middle of a revenge tale, even if don’t understand the villain behind it. We’re blind because, just like the prose of Termination Shock, our lives are darkened with so much detail that we can’t read the signs around us.

And, besides, it’s much more tempting to look toward the light-hearted adventures that brighten our day-to-day than slog through the boring realities of how things actually work.

Hard YES to these points about hard sci-fi. I've been reading the first Dune trilogy this summer, and it's sci-fi that knows how to frame the logic between the story-world and its objects by depiciting those objects' use through action and propulsive dialogue, rather than dropping exposition dumps from the top ropes. Seems like Stephenson's caught in a cul-de-sac of self-regard - too much time with Thiel and Zuck, I'd posit. But that feral swine plotline seems like a doozy.

“Revenge of the Pigs” probably has to be written.