R.L. Stine's Writing Rules for an Illiterate Generation

Dispatches from a post-literate nation

Technology has ruined a lot of things that make for good mysteries.

- R.L. Stine

When I was a kid in the nineties, my hopes and dreams were delivered to me in color-blasted pamphlets on behalf of the Scholastic Book Fair. These color-blasted pamphlets helped me discover a lifelong passion for reading by introducing me to series like Calvin & Hobbes, Animorphs, and Goosebumps.

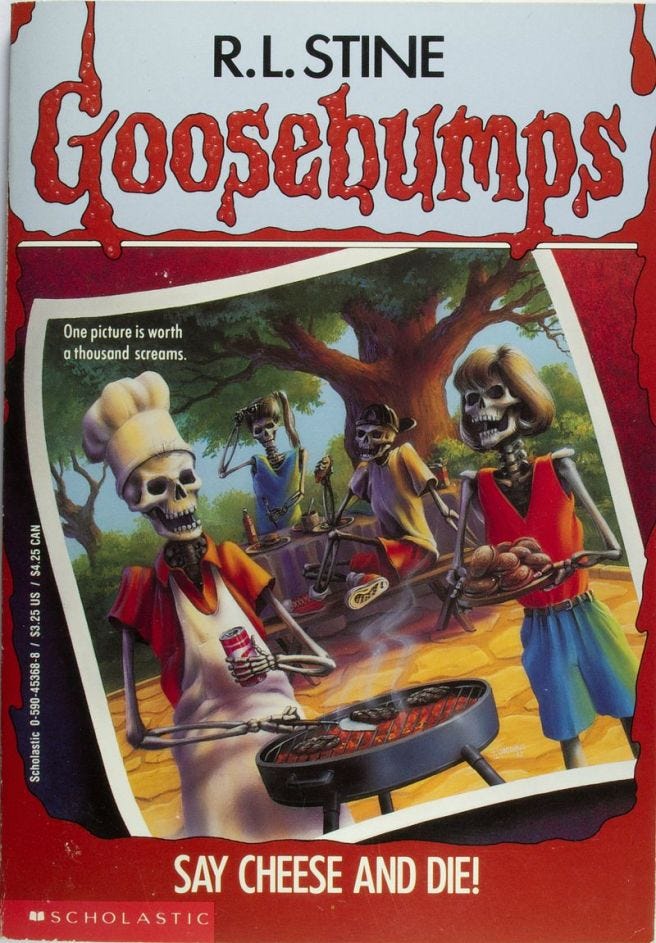

It was a golden age for children’s books. From 1992 to 1997, Goosebumps author R.L. Stine published 62 books. That’s a rough rate of 12 books a year. As of today, the series has sold 400 million copies worldwide. In elementary school, Goosebumps books served as my constant companions. When I started at a new school after my parent’s divorce and took a bus full of strange new kids, all it took was a book to make me perfectly content and perfectly less alone.

I thought about these moments when I heard that kids reading for pleasure has hit a record low.

Age of the Post-Literate Youth

Today, research estimates that 40% of American students can’t read at a basic level. Because when reading isn’t fun, kids don’t read as much. When kids don’t read as much, they don’t get better at reading. When they don’t get better at reading, they don’t read as much. So the cycle continues. I don’t think this trend is even about illiterate versus literate populations. It’s about the fact that books have to compete with phones and video games for pleasure. They’re failing. And so we are entering a post-literate age.

The UK-based National Literacy Trust recently reported that only 35% of 8-18 year-olds enjoy reading in their spare time. This was not a low-budget survey. More than 75,000 kids across the UK were surveyed. Two out of three of those kids simply don’t think of reading as something to do voluntarily. And for fun? Forget it. There are phones to thumb.

Reading for pleasure makes kids better readers. As The Guardian explains :

The NLT found that twice as many children who said they enjoy reading in their spare time have above average reading skills (34.2%) compared with those who don’t enjoy it (15.7%).

Children who read in their free time at least once a month said that it helps them to relax (56.6%) and feel happy (41%), learn new things (50.9%), understand the views of others (32.8%) and learn about other cultures (32.4%).

Here’s the cherry on top: other research has confirmed that reading makes us less lonely. For younger generations who aren’t reading as much, who are more lonely and depressed than ever before, this is not great news.

This is great research to start a debate that allows everyone to air their specific grievances. The debate topic is simple: Why are kids not reading for fun as often?

I’ve seen two answers to the question:

a lack of good, honest, unapologetic adventures for young readers thanks to ideological publishers and tyrannical sensitivity readers favoring issues-based books about oppression

the fact young Americans spend nine hours a day on their phones and get more than 200 notifications a day

The first answer is unserious outrage bait. Even if every modern book for kids is an uncompelling romp of righteousness, there is a rich catalog of books from the nineties and that can serve the purpose of high adventure fun just as easily. These books have a lasting impact. Just ask any millennial who knows what Hogwarts house is their forever home.

The second question is a question about how reading really functions. The wholesale decline in kids reading for pleasure and catastrophic national literacy rates are not because there’s lack of fun things to read. It’s because there are more fun things to do. Kids, like everyone else, are replacing books with another medium when they have free time.

In this millennium, novels, a sixteenth-century medium, are competing with new mediums for media. It might be as simple as that. And if it’s as simple as that, the answer is simple: make kids bored again. Or at least prove that books can be as fun as video games and phones. This is when it’s important to go to the source: Goosebumps.

Fear, Fun, and R.L. Stine

Let’s say it’s possible to write something good enough to replace a kid’s phone. What does it look like? How can someone even write something so powerful?

In an interview with R.L. Stine, the author of Goosebumps, he gives four key tips for writing for kids… and/or an illiterate generation.

Here’s how R.L. Stine does it:

1. Get Rid of the Phone.

Devices that have all the answers and get in touch with everyone in an instant are prophylactics of plot as much as they are prophylactics of social lives. In R.L. Stine’s view, a book has to get rid of the phones to even work.

As he explains:

You have to get rid of the phone when you’re writing the book. Everyone has a phone now and everyone can just call for help. In some ways, it’s much more challenging now.

2. Keep Your Theme Simple.

In Stine’s world, things are simple: people are scared of stuff and it’s usually the same stuff. Doesn’t matter what year or what generation. When you’re writing for your reader, remember to keep the theme a simple.

As he explains:

The lucky thing about horror is that the things that people are afraid of, it never changes. Afraid of the dark, afraid someone’s in the house, afraid someone’s under your bed—that’s the same.

3. The Message is the Minimum.

As anyone who has been to church, school, or jail knows: the more lessons, the less fun. A good book is an adventure into a world that is a lesson unto itself. By bringing modern messages about modern issues into the story, the story breaks immersion and hurls the reader back into the real world.

R.L. Stine has a simple rule for writing for teenagers:

No messages, except that the ordinary teenagers faced with horrible things can use their own wits and imagination to survive, to triumph. That’s the only message that I ever put in. There’s a lot of real-world stuff that I don’t put in Goosebumps or Fear Street. In Goosebumps, no one ever dies. In Fear Street, you want to make sure that it’s a fantasy that’s not too real. There are no drugs in Fear Street. There’s no child abuse. There are hardly even divorced parents. Other teen horror writers have done a lot with teens with drugs and that kind of thing, but I don’t do it. My basic rule is they have to know it’s not real. That it’s fantasy.

He’s even had direct reader feedback when he tried a tragic and unhappy ending in a Fear Street book. The kids, as it turned out, didn’t appreciate the nuance. Teens get gray areas in real life. They don't want it in their stories.

As Stine recalls:

They want happy endings in these. I learned my lesson that time. The kids really turned against me. It was immediate. I got these letters. “Dear R.L. Stine, you moron. You idiot. How could you do that? When are you going to finish the story?” They just couldn’t accept it. I would do school visits, and that book haunted me. The hand would go up: “Why would you write that book? Why did you do that?” Maybe it’s changed, but I’m not going to try it!

Back to Basics

In college, I had one class that destroyed my ability to write like none other: Literary Theory. In addition to traumatic events that are impossible to come back from like being introduced to Foucault or Derrida, the class shattered my prose style with an obsession over who is the narrator in any given scene. Once you start thinking about who is reading the story and who is writing the story, you’re anywhere but in the story.

The intellectualization of literature is the death of literature. Self-conscious plotting is dirt on the grave. Want to give people goosebumps when they think of reading again? Start having fun. Because if the writer isn’t having fun, the reader never will.

You bring up many good points here, but there is one more to add: If parents want their children to read and be more literate, then the parents themselves need to set an example. Children learn much more from watching what their parents do than from what their parents TELL them to do. I became a reader because my mother spent many hours ignoring the housework and reading, and she made it seem so pleasurable that I started reading, too. What troubles me is the high percentage of parents I see who are on their phones in the library while they're expecting their kids to pick out books, and the number of parents I see buried in their phones instead of chatting with their children when they're in a park or playground. You can't expect your children to acquire--and enjoy--language without that kind of modeling.

100% in agreement with Holly's views 🫡 Modeling reading habits is something we have to get back to: if the act of reading is framed as a school thing or a chore, not a regular part of a healthy life of the mind, then the battle's over before it's begun.

This piece had a ton of emotional resonance: Tolkien and Hergé and Brian Jacques were not only touchstones of childhood for me, but sites where my sense of myself and my world could expand in four-dimensional Technicolor. "A good book is an adventure into a world that is a lesson unto itself" was the standout insight - the best way into a person's head is through the heart.