In Defense of Repression II

On the path of psychology less traveled

There is no man, however wise, who has not at some period of his youth said things, or lived a life, the memory of which is so unpleasant to him that he would gladly expunge it… We do not receive wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness which no one else can make for us, which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world.

-Marcel Proust, Within a Budding Grove (1919)

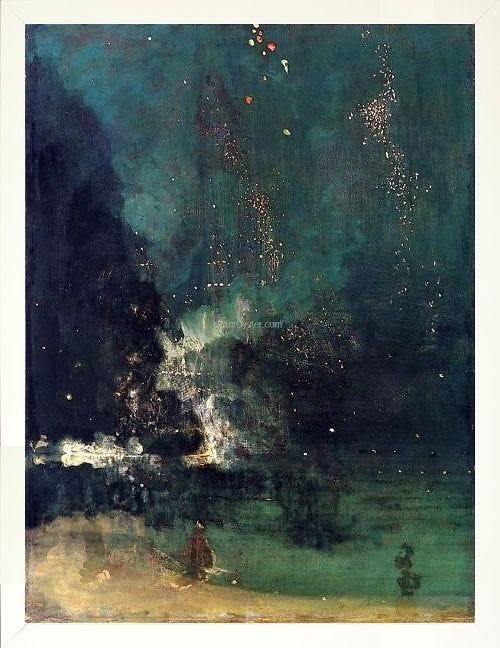

Proust’s Impressionist painter Elstir, a character inspired by Impressionist painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler, explains his troubled and regretful past - and the old selves he now represses - as a process. In his “journey through the wilderness,” he recognizes old selves and leaves them behind. Repression in Elstir’s view is a tool to be used in building a new self. This pain is accepted and integrated, not expressed.

Cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker helps us look at repression on a macro scale, theorizing that repression is not just good for self-growth, but good for society. If we don’t agree on what to repress as a society, Becker sees a future where we disagree on the fundamental truths of right and wrong, beauty and vanity, being and emptiness. In yesterday’s Litverse, we covered how Becker’s The Denial of Death (1972) argues that without the shared heroisms and stories given to us by religion and community values - things that, by default, require repression of our own desires for the sake of something bigger - a secular society turns to psychology for meaning.

In other words: by freeing us from the clear-cut guidelines for a greater purpose that are offered to us by a religion or a society, Becker believes psychology personalizes every individual’s meaning to a point where no shared heroisms are possible because what we believe to be “true” is a mirror for what we decide is our “self” above all. In telling the stories of that self to a world too busy telling its own stories to listen, it is expression, not repression, where we find our purpose: to be the hero of a self-made myth, we must find followers. Putting the inner self at the center of the world, rather than finding ways to embrace outer space, Becker argues, is a lonely universe.

With no variables valued by shared religion or nationalism or culture, The Denial of Death postulates that we project our beliefs and our values into the objects and people around us to discover our purpose. That said, projection today is almost always seen as a defense mechanism. As contemporary psychology describes it:

Projection refers to a type of defense mechanism in psychoanalytic theory, whereby unacceptable feelings and self-attributes within an individual are disavowed and attributed to someone else. So, for example, an individual may hold aggressive or murderous thoughts and feelings which are unacceptable to their sense of self. In order to defend against a threat to their self, they disavow these feelings and project them onto others, who are then perceived to be hostile and aggressive. Projection is involved in the process of othering, where the other comes to represent the opposite of the self, often that which is disavowed in the self.

Becker’s interpretation is different. He frames projection as a fundamental good that gives us the cause and willpower to follow our purpose by allowing us to pour ourselves into the people and places and things outside ourselves and therefore understand and prioritize the outer world as a part of the inner self and live for something greater. We project ourselves into the things we love most: partners, pets, children, friends, hobbies, careers, philosophies, social channels and devices and video games and houses and adventures and memories and instincts. This is an anthropologist’s take on mind and meaning: Projection makes us live, learn, and love things greater than ourselves by satisfying the irreducible biology of our narcissism.

Psychotherapist Sigmund Freud, who figures into The Denial of Death as an antihero to be respected but not revered, helped popularize the theory of projection even if, as always, he presents “projection” with orifice-adjacent terminology, describing it as:

A process of evacuating not only excitation but feelings and representations or thoughts which are linked to that excitation. What is projected is then located in the external world and may be experienced by the individual as persecutory, forming the basis of paranoia.

This is where it gets interesting: in The Denial of Death, we see Becker casually challenging the traditional definition of projection by removing the contention that to project is a symptom of paranoia or, actually, even bad at all. That’s because, in believing that repression is necessary, he thinks the delusions caused by projection are where we do, in fact, find our purpose. How can we hate someone or be apathetic to something that we decided is part of ourselves?

In his anthropological acceptance of human nature as selfish and narcissistic but not moralizing on motives, Becker architects an optimistic definition of projection. He believes we project to be fulfilled. Narcissism is biology and that’s how we survive. To find beauty, we fulfill that base instinct through what could creatively be called a transcendental use of narcissism by convincing ourselves everyone and everything around us is something that is a part of us and therefore worth cherishing and protecting.

Like many theories Becker presents in the book, this is a sentiment about projection lost to time. Modern readers likely view projection as something to be avoided, because it is an act of losing the self to someone else. In Becker’s view, that’s the whole point. The Denial of Death, a work created in the era of the Vietnam War and flowe power, is at times a sphinx of lost psychological theories. This is why it’s such an absorbing read: even when Becker is insulting psychologists as “simplifiers” and “prophets of unrepression,” readers get a thrill in uncommon thinking.

Becker’s philosophy of mind is different and forgotten, because his inspiration, too, is different and forgotten: the long-time friend, co-author, and rival of Sigmund Freud: Otto Rank (1884-1939). Rank’s Trauma of Birth (1924), in presenting an opposing theory to Freud’s “Oedipus Complex,” made Freud incredibly angry, to the point where he was telling people he was “boiling with rage” at the challenge. One might find it to be a testament to the cultish predilections of Freud’s brand of psychoanalysis in that it is Rank who is seen as an outsider when he wonders if Freud’s theory of the Oedipus Complex, which assures families that all sons are attracted to their mothers and angry at their fathers, might just be a little silly.

Rank’s methodology of mind insists that it is we who are in control of our minds and how they work. He regards childhood as an experience, not a foundation for predestination. Our decisions and our perceptions are our destiny. As summarized:

Rank used the term psychotherapy, rather than Freud's psychoanalysis, and he focused on choices, responsibilities, conscious experiences, and the present, instead of drives, determinism, the unconscious, and the past.

Rank’s career led him to go on to become a psychoanalyst for famous artists, including Henry James, and develop a Romantic understanding of our mind thar culminates in 1932’s Art and Artist, a delightfully dense work which we’ll revisit on Litverse in the future. Becker clearly adores Rank’s radioactive combination of deism, sociology, anthropology, and existentialism. This explains the core of all the themes found in The Denial of Death.

Becker’s insistence that repression is the key to living a fulfilling life cannot be separated from his experience as an infantryman in World War II. Military service categorically requires repression to engineer the sacrifice of the self for the greater good. Add to the mix that Becker helped liberate a concentration camp and we migt understand the value of repression for someone with his experience. The Denial of Death becomes, in a way, more beautiful when seen as a man making sense of his own mind and the world it creates. Repression is translated by creation. Becker teaches us why repression becomes such an effective methodology for some people, but completely ignores that the mental models that are cures for some are curses for others. Not everyone can so easily hide from themselves.

In dwelling on the defenses of repression proposed in The Denial of Death, I am reminded of the bottomless chuckle of Kurt Vonnegut that peppers every part of the beautiful documentary about his life. Visiting his old high school, we follow Vonnegut to a wall of names dedicated to the soldiers from his graduating class who died in World War II. He laughs as he proclaims their fates: died in a training exercise, fell out of a plane, Battle of the Bulge. In lingering on the names, he goes quiet.

On the train back, Vonnegut stares out into the distance of the horizon with misty eyes. Do you think about it? Were you traumatized by it? The interviewer asks. No, no, not at all, Vonnegut says, and in that moment we can see that two things can be true and false at once. In the silence of Vonnegut’s gaze, the viewer is left to wonder whether we are seeing a moment of reflection or a moment of repression, a space where Vonnegut, a prisoner of war during the Dresden bombing who had to shovel the corpses of innocents in the aftermath and Becker, an infantryman who had liberated a concentration camp, both find their peace and their purpose.

Repression is good for some people, for some reasons, some of the time. Others, from patriots to priests to politicians, can so professionally repress opposing beliefs that they are granted unwavering faith in their greater purpose. We all repress something every day, from federal agencies to iPhone user, meat eater and oil-powered car owner. This is the blessing and the curse of infinite awareness in the connected age. If we, even for a second, take a time to contemplate the impossible vastness that spins the web of life, we may understand the cosmic necessity of repression as what Becker believes it to be: a survival instinct.

The Denial of Death delivers a disjointed but optimistic assessment: Repression gives us the power of choice and control over our experiences. Becker’s secret to a happy life is to find the “boldest creative myth” that inspires and motivates us to live our truth and - yes, this is part of it - embrace with enthusiasm our narcissism as a survival instinct but only a narcissism that motivates us to project meaning into the external world, not our internal world, to find ourselves in others.

Repression is acceptance that the self is a liquid rather than a solid, and always becoming air. It is up to us to reflect the brilliance of our greater being outside the self and, in growing souls in what we know to be sunlight, accepting the shadows as salvation by another name.

I don't think Becker's beliefs as expressed here are at odds with modern psychology and clinical therapy; he's merely taken the names of denial and projection and generously redefined them into much broader modes of thinking and behavior.

For example, Hemingway's advice doesn't support a case for denial, but rather a life of acceptance and awareness: to see both traumas and strengths as they are and nothing more, stand at an artistic distance from overwhelming emotion, and put forth your best efforts toward what you value. This is exactly in line with acceptance and commitment therapy. Moreover, in fiction, denial is an artistic flaw: it disrupts the vivid continuous dream of storytelling and alerts the reader to involuntary intrusions of the writer and his human flaws. It seems that Becker is conflating denial with compartmentalizing one's disruptive emotions in order to prioritize meaningful activity.

I'd argue that most people agree with Becker's common sense argument for seeking meaning through a cause greater than one's self. What remains dubious is the surface-level contrarianism.

Never heard of Rank - seems like an interesting foil for Freud. And you put a nice point on things in summarizing Becker's stances. More damn fine work 🤝