If people do not return to the office when they are able to return to the office, they cannot remain at the company. End of story.

-Elon Musk

One of my friends is a tech CEO with a company headquartered in New York City. In 2019, he signed a lease for an office in the World Trade Center Halfway through 2020, any company with an office seemed dumb and, a year later, he told me gleefully that he had gotten out of it.

”We’re never going to have an office again,” he said. “That'll make us really competitive when we’re looking for talent, especially the people who never want to commute.”

When I met him at an East Village bar recently and asked how the remote-only workforce was going, he pulled his pilsner under the rotting roof of the street-side shed and said, “We’ve seen a sixty percent drop in productivity, but we’re saving money. So it’s worth it.”

This is the debate between return-to-office sympathizers and remote work true believers: what, exactly, makes an office worth it?

There’s got to be something: 90% of companies plan to bring employees back to the office at least a few days a week. Today, about a third of Fortune 100 companies revoked their remote work policies. Depending on who you listen to, this is a matter of perception, productivity, or real estate portfolio.

Do you feel more productive at home instead of a noisy environment with bothersome co-workers? Too bad. The facts aren’t on your side, if you believe the right research. As the LA Times reports:

It’s true that widespread studies based on standard measures of efficiency have found that fully remote employees are 10% to 20% less productive than those working on company premises. Challenges related to communications, coordination and self-motivation may be factors in the decline.

Given the data, my friend’s estimate of a thirty percent drop in productivity doesn’t seem far off. Remote workers might kick and scream about the advantages of the arrangement, but it’s still far from normal.

In August 2023, 12% of US workers and 11% of private businesses were fully remote.

More than 4.7 million U.S. workers are remote at least half of the time

65% of workers want to be remote all the time, while 32% prefer a hybrid work schedule

About 32.6 million Americans are estimated to be working remotely by 2025

Given the numbers, a return-to-office mandate is a return-to-normal policy.

Remote work is good for a certain kind of individual, but not evidently not good for the company as a whole. This makes it a sensitive topic for people of a certain class, profession, age, and homeowner status. Millennials and Gen Xers with families and careers will defend to the death the idea that rolling out of bed ten minutes before a video call wearing pajamas has no effect on their passion for the company mission, the innate meaning of their life, or their boundaries between the personal, the professional, and the spiritual. These comfortably mid-career employees scorn the concept of returning to stressful commutes, punishing open office environments and battles over conference rooms. Memes memorialize “office culture” with catchy clips of stale donuts, fever-eyed founders, and fields of desks aflame with unfulfilling fluorescence.

The argument against in-person, real-life experiences with co-workers comes back to same scene: a person at a desk in an empty office building on a Zoom call who could have easily done the same thing at home.

“I came all the way to the office for this,” the person says about this pointless journey. What did they see on the way to the office? How did they mentally prepare before stepping out the door? What did they feel in the air as they spent time between destinations when they were alone in the liminal limbo of a commute? Who did they greet on the way to the desk and how did they smile? How did they dress and walk and talk? What did they see? What did they touch?

Our resistance to office culture is a resistance to any and all interactions that we decide are an inconvenience. Remote work follows the modern wisdom that the journey is not the destination. The destination is the destination.

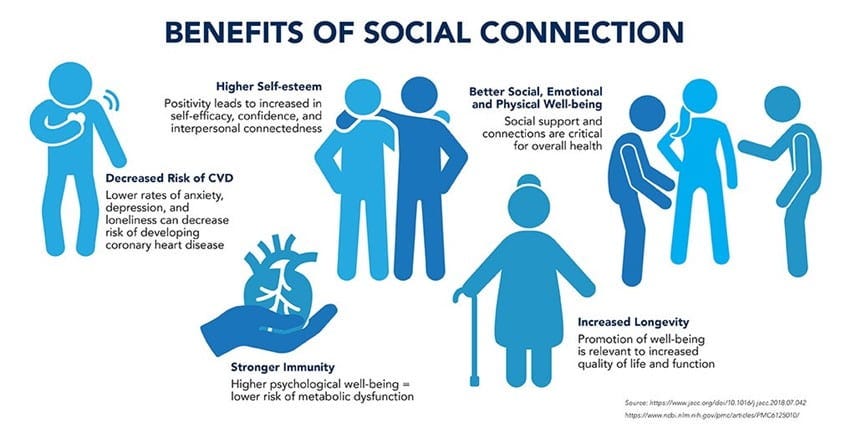

Despite all the overwhelming evidence that the isolation of internet makes people lonelier, sadder, and lamer, remote culture is based on the belief that if something delays the gratification of the task at hand - or is uncomfortable - it’s not worth doing.

(More on that in Litverse’s rant on Gen Z, “Lonelier Than Ever? Maybe It’s Your Fault.”)

The stale bread of “office culture” is impossible to defend, but the numbers of what we watch don’t lie: in 2020, the golden age of remote culture, The Office became the most streamed show on Netflix, reaching 57 billion minutes. In 2023, the legal drama Suits - set in a skyscraper office in New York City - beat that record with 57 billion minutes. We don’t long for the experience of working in an office but the experiences that come with it.

Gen Xers and millennials, awash in apathy, have gotten mossy with middle-age. Content with the social circles they gained through school and the professional network gained through office hours and happy hours, older workers forget that Gen Z is entering a workforce that mimics the same teaching environment that failed them.

Remote Lessons, Remote Life

There’s fairly good consensus that, in general, as a society, we probably kept kids out of school longer than we should have.

- Dr. Sean O’Leary, New York Times

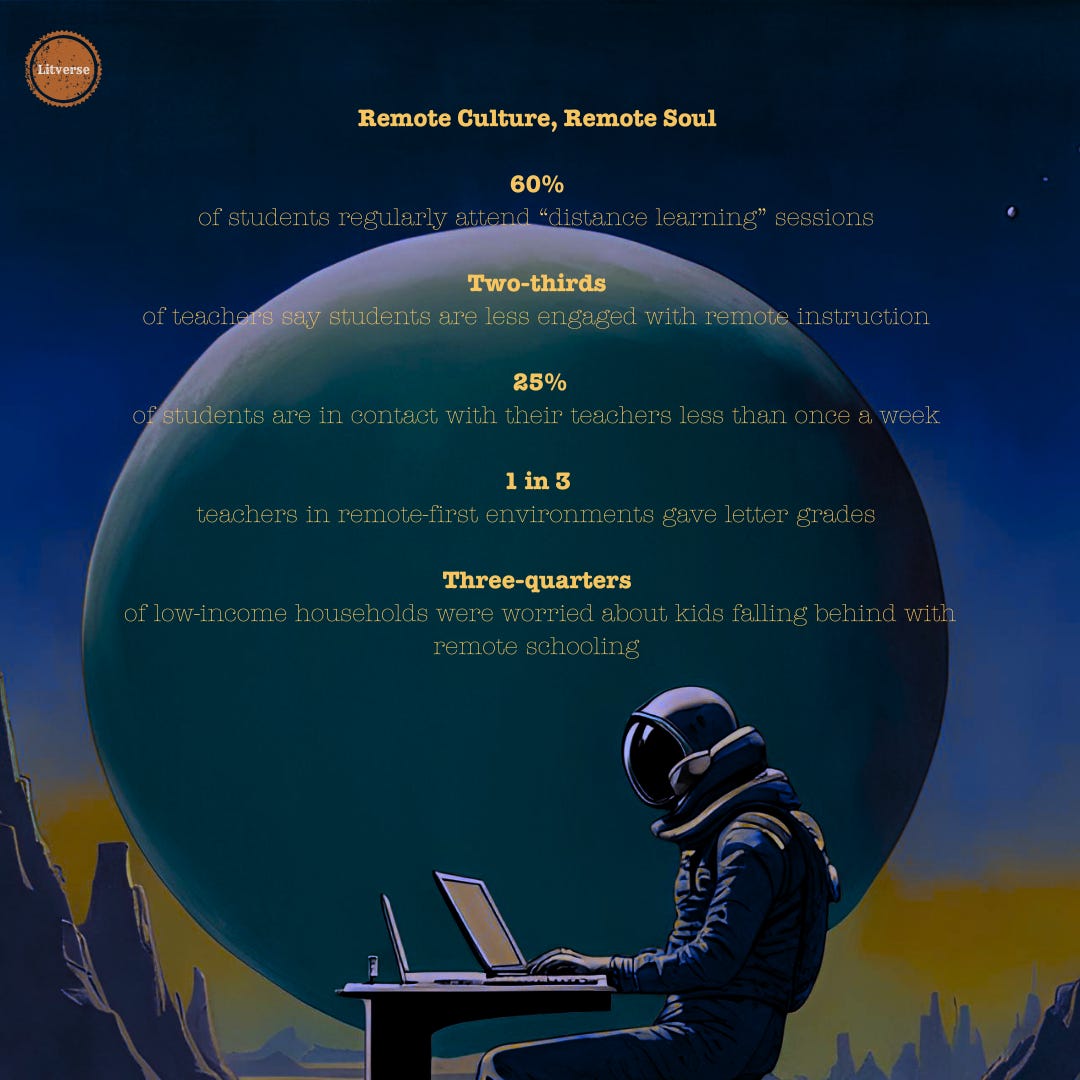

In a remote learning environment:

Only 60% students regularly attend “distance learning” sessions

More than two-thirds of teachers say students are less engaged with remote instruction

25% of students are in contact with their teachers less than once a week

Only a third of teachers in remote-first environments gave letter grades

Three-quarters of low-income households were worried about kids falling behind with remote schooling

Replace the word “students” with “employees” and “teachers’ with “managers” to humor the message here. This is the funniest part of remote work: the bold belief that employees thrive in alienation when a national back-to-school movement, with no resistance, declared remote learning to be an utter failure.

In a remote-first world, the job networks, happy hours, social opportunities, friendships, romances, memories and moments are impossible for new college graduates. Anyone who has encountered a recent college grad on a video call should know this firsthand: with no real-life experiences and no real-life interaction, there’s no real-life emotion to make people feel like what they do matters... if they know how to do it at all. What’s the point of caring about something that comes and goes with a click whether commerce, conviction, career, or social circle?

Remote work begets a remote soul where the days are as meaningful, as substantial and significant and social, as a tab on a browser or an app on a phone, and gives us a workday streaming so steadily there’s no time to think about what we miss in the current.

Want more context? Read about the dark side of hustle culture.

One consequence of remote culture is the endless meetings. There's never a quick 5-10 min knock on the door anymore, it's always the default 30 min calendar block. Oh, you have 30 mins in between 3 hour meeting block? Allow me to not allow you to quench your thirst because I need help filling out some bureaucratic form. I find the culture around remote work to be exhausting and it has nothing to do with commutes.

I still think we're not even looking at the mid-term for this change. If companies that are fully or mostly remote are indeed less productive than more in-person companies, then we are going to see remote work dwindle in the long run. Or maybe not. If fully remote workers are less productive, they might be willing to forego higher pay in return for a fully remote role in a low-cost of living area because they prefer that lifestyle, and companies may make room for that. Think about the fact that workers in the richest European countries are about as productive as American workers while earning a lot less. To some extent, that's because they work significantly fewer hours than Americans and generally like it that way.

There's also the question of commuting, which in the US is overwhelmingly single-occupancy cars. The benefits of giving up long, wasteful commutes are often touted but there's some evidence (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0965856421000574) that frequent telecommuters actually drive more. I think what's going on is that people find commuting to be more stressful than other kinds of travel and will substitute the latter for the former.

That said, there is much that is J.G. Ballard-esque about a career that proceeds entirely from a private home, with no dress code or hygiene expectations, where the office is two monitors, and your colleagues are voices on a headset or talking heads on Teams. From the WELL onwards, nerds dreamed of a frictionless, remote, disembodied form of communication that would be less ambiguous and more rational than what came before. I think a lot of the debate about remote work would make sense as attempts to try to bridge contradictions. Remote work offers a lot of benefits to a lot of people, there's no doubt about that. On the other hand, there's an innate sense that remote work might be capital-b Bad for us, especially for the young, single, and urban. People have an innate sense of that shown by the fact that we're universally rejecting virtual education.